Printed American broadsides of the 18th and 19th centuries—what we might think of today as “posters”—were an important public means of spreading news and information within a community.

A broadside might print a political manifesto, a religious sermon, a military declaration, news of a great battle, or a Presidential proclamation.

A broadside might advertise a newly arrived shipment of goods or a new production of a play or circus. Merchants and inventors used broadsides to sell their wares or to attract investors.

American broadsides fall under the broader category of historical ephemera—printed items created and intended only for temporary, fleeting use. These ephemeral artifacts documented the beliefs, activities, and concerns of a very specific time and place in American history.

Eighteenth and nineteenth century American broadsides were public notices and announcements; mass media in an age where the “worlds” in which men and women lived were much smaller and less connected.

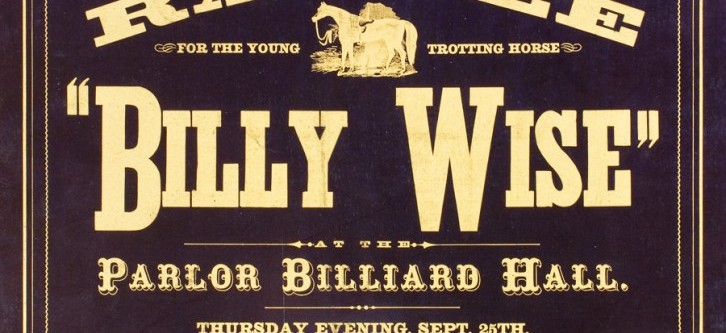

From an American broadside circa 1854 printed in Charleston, South Carolina. Illustrated broadsides from 18th and 19th century America are desirable, as are broadsides lettered in color.

Unlike a book, a broadside’s authorship often was anonymous or obliquely suggested. This broadside from the American Civil War denounces Copperheads, those individuals whom’s loyalty to the Union cause was of dubious nature.

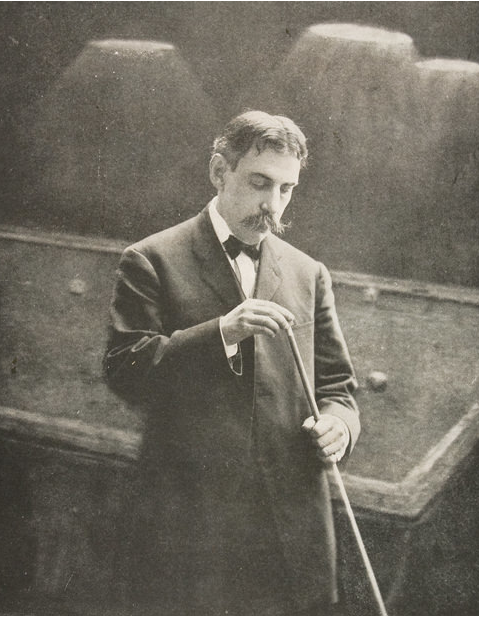

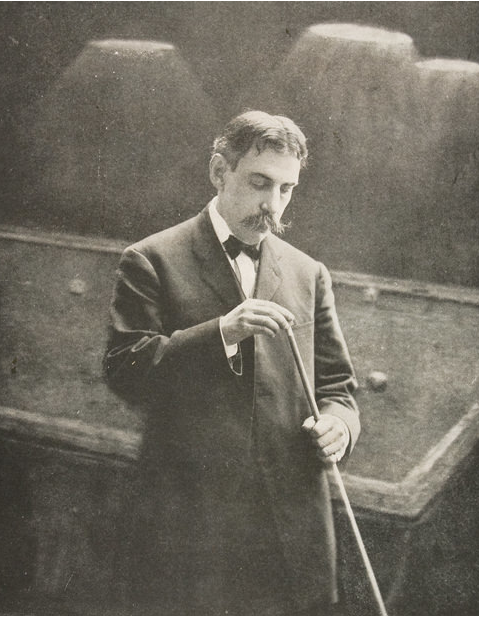

(Image detail) By the 20th century, printing technologies in America had grown remarkably. The idea of a text-only broadside as being an important source, a primary channel of disseminating information, would be challenged by photography radio and eventually television. Here the halftone process is used to show portraits of five famous billiard players.

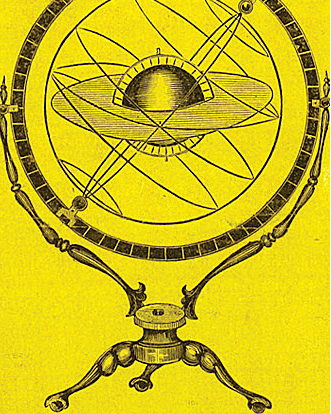

(Image detail) American broadside advertising “Vale’s Improved Globe and Celestial Sphere…Manufactured at His Nautical and Mathematical Academy, 94 Roosevelt-Street New-York.”

Nailed up on courthouses, public taverns, and post offices, American broadsides were also hung up in shop windows or handed out in the streets (hence the term handbill).

Newsboys printed poetical broadside greetings and gave them to their customers with the expectation of a tip. Medical quarantine notices served as public warnings.

Printed on one side of a sheet of paper, American broadsides attracted attention by being large in size and by using large printing type and/or illustrations. In the 18th century, they were often crude affairs, perhaps illustrated with a simple cut with haphazard letterpress printing.

Printing technologies improved, especially in the second half of the nineteenth century. Broadsides became larger still, more poster-like, and were often printed in color by lithography.

American broadsides convey their contents by means of the printed word. They are often the starting point for historians who are trying to understand the events and concerns of the past.

Graphically, as visual Americana, broadsides are emblematic of their times. Consider the plain printing of John Dunlap’s 1776 broadside first printing of the Declaration of Independence or the “wanted poster” for the conspirators who murdered Abraham Lincoln, or Uncle Sam’s I Want You poster.

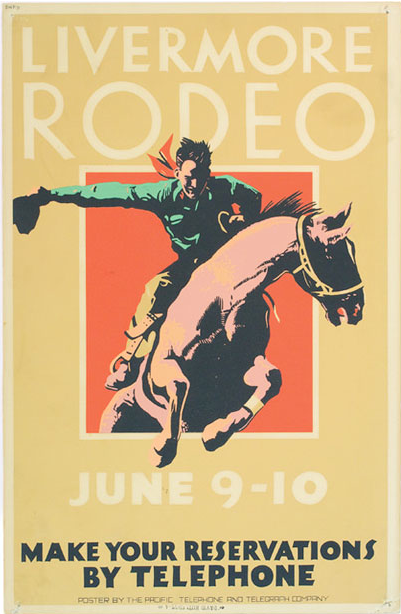

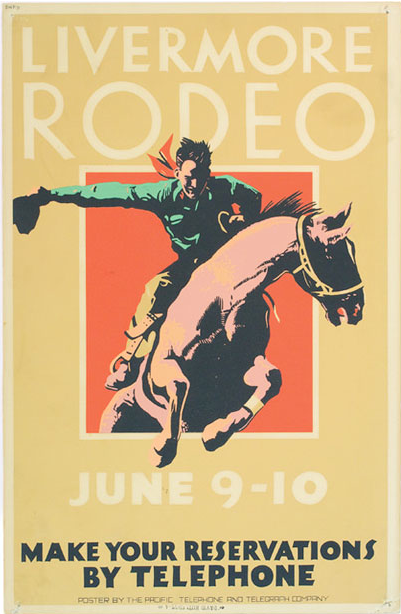

An all-American cowboy rodeo, the perfect theme for this colorful California broadside. Described as a “Poster by the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company” its purpose was the same as many broadsides printed in the previous century: to be posted and read; here, likely on PT&T’s very own telephone poles.

Especially desirable are 19th century American broadsides with stunning chromolithography. Highly-esteemed, Louis Prang was a master of American chromolithography. Thisbroadside was in remarkable condition with vibrant color.

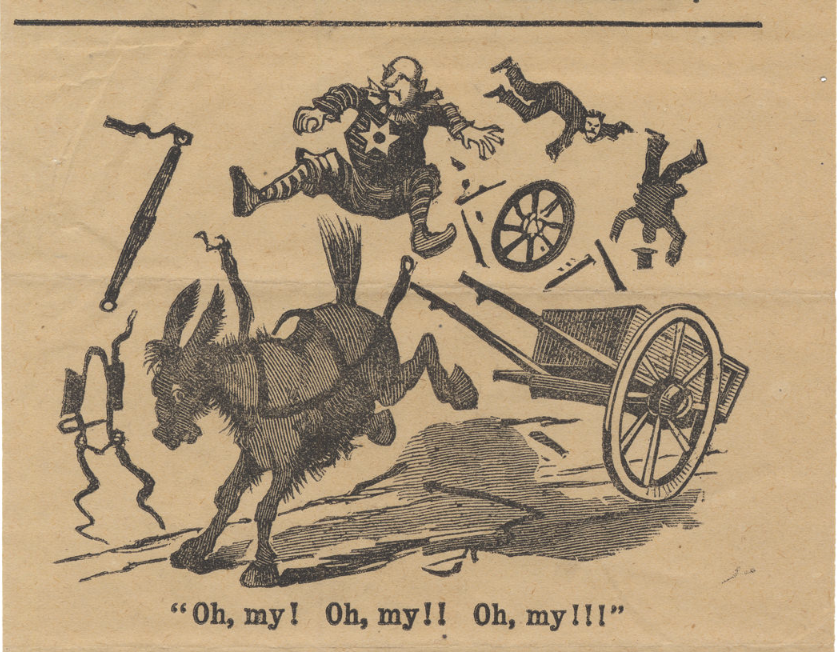

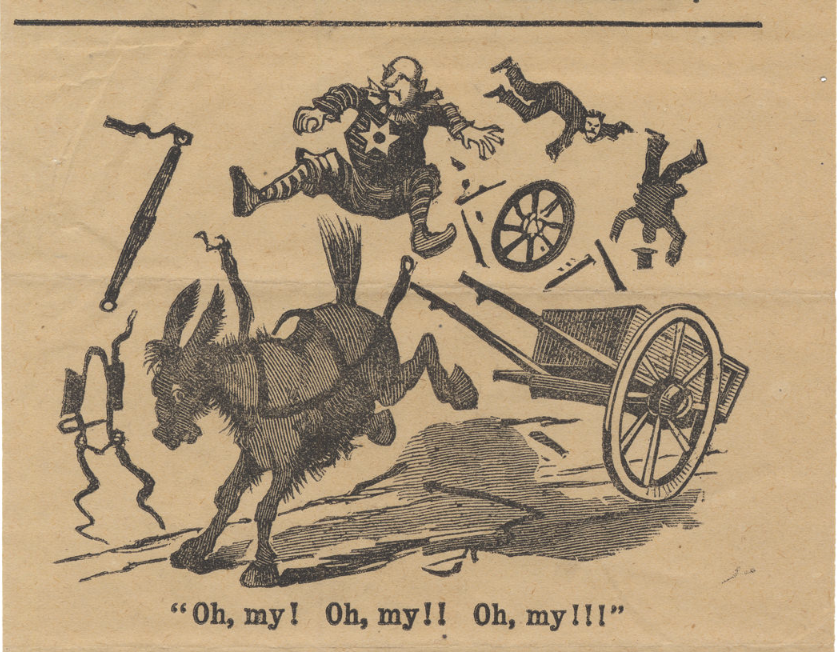

This 1881–1882 Brooklyn broadside used caricature and humor to induce Brooklynites into viewing a performance at Hyde & Behman’s Theatre. The theatre was situated not far from the Brooklyn Bridge.

This post originally appeared in Ian's blog, Collecting Rare Americana. It was reposted here with the author's permission.

Check out more broadsides here: http://bit.ly/1ysIx3u