Carousel content with 1 slides.

A carousel is a rotating set of images, rotation stops on keyboard focus on carousel tab controls or hovering the mouse pointer over images. Use the tabs or the previous and next buttons to change the displayed slide.

first edition

1552 · Venice

by TWO EARLY WORKS ON HOUSEHOLD ECONOMY BOUND TOGETHER

8vo. [8], 64 leaves. Collation: *8 A-H8. Printer's devices on the title page and at the end. Woodcut historiated initials. Roman and italic type.

Rare first edition, edited by Girolamo Ferlito who signs the dedication to Bernardino Sanseverino, Duke of Somma, from Venice on 15 May 1522. The work was reprinted by Arravabene the following year.

Caggio's Iconomica is written in the form of a dialogue that takes place over the course of two days between two interlocutors, the aged and wise Apollonius and the young and impulsive Monophilus. In the form of benevolent instruction, Apollonius tries to persuade Monophilus of the need to form a family. To (truncated) this end, the author analyses a wide range of issues relating to family government, such as what the family is; the differences between the prince and the father of the family; the qualities and virtues required of a woman to be an excellent wife and mother (Caggio shows great respect and admiration for the female gender); the differences between the two sexes that make them complementary (Caggio advocates relationships between men and women characterised by mutual understanding and cooperation); the praise of marriage; the education of children (he also discusses the lack of good schools in the Kingdom of Sicily); the importance of cultivating good friendships; how to deal with servants; how to preserve and increase wealth; the value and development of agriculture; the duties of the father in order to make the family administration prosperous; and so on (cf. G. Ratto, Introduzione, in: P. Caggio, "Iconomica", Naples, 1986, pp. 11-82).

Paolo Caggio was born in Palermo around 1525 into a wealthy family of senators. He studied law and held several public offices during his career, including the post of secretary or chancellor of the senate. He apparently never left Sicily during his lifetime. The publication in Venice of his works (Ragionamenti, 1551; Flamminia prudente, 1551; and Iconomica, 1552) was undertaken by his friend Ottaviano Precone, Bishop of Monopoli. In 1549 Caggio founded the Accademia dei Solitari to promote the spread of the Italian language in Sicily through the study of the works of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio.

"The play (Flamminia prudente, Venice 1551) is thus to some extent the 'female' counterpart to Caggio's Iconomica, in which male speakers discuss male prudentia and which was aimed at an educated and thus predominantly male audience. Against this background, the choice of genre also appears to be gendered: the dialogue (Iconomica) is addressed to male recipients, the entertaining and educational play (Flamminia prudente) to a mixed audience - although in the latter case the economic-didactic part is explicitly addressed to female viewers, whereas the literary satire is presumably addressed primarily to a male audience (and especially to scholars). This can be explained not least by the fact that, compared to the theoretical discourse, the theatrical performance reaches a potentially wider circle of female recipients, namely those women who have little literary education or are illiterate. Especially in its final form, the performance of the drama also has a liveliness that treatises and dialogues, because of their written form, cannot achieve. In addition to this, catchy linguistic register, brevity and entertainment enable a comedy such as the Flamminia prudente to appeal to a completely different audience than the theoretical genres" (Ch. Schaefer, Weibliche "prudentia" auf der Bühne. Zur Inszenierung ökonomischer Konzepte in Paolo Caggios "Flamminiaprudente" (1551), in: "Das Haus Schreiben. Bewegungen ökonomischen Wissens in der Literatur der Frühen Neuzeit", Ch. Schaefer & S. Zeisberg, eds., Wiesbaden, 2018, pp. 145-146).

Edit 16, CNCE8270; USTC, 817608.

(bound with:)

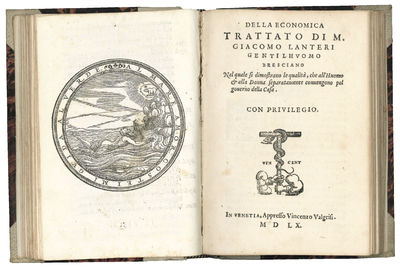

LANTERI, Giacomo (d. 1560). Della economica trattato di M. Giacomo Lanteri gentilhuomo bresciano nel quale si dimostrano le qualità, che all'huomo et alla donna separatamente convengono pel governo della casa. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1560.

8vo. [32], 171, [5] pp. Collation: *-**8 A-L8. The last leaf is a blank. Printer's device on the title page and on l. L7v. Errata at l. L6v. Woodcut historiated initials. Roman and italic type.

Rare first edition, dedicated by Lanteri to Renée of France, Duchess of Ferrara.

According to Lanteri, the "economica" or household economy is a science whose importance and necessity is demonstrated by the ruinous fortunes of so many families over the years. Lanteri, an expert in military architecture, describes the characteristics of the family home according to social status, from the noble to the merchant; he also discusses at length the different roles of father and mother, the choice of servants and the education of children. As for the actual economy, while Lanteri does not consider it disreputable for the pater familias to engage in commerce, he considers agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting to be the most noble and appropriate activities for him. Like Caggio, Lanteri also believed that the domestic and public economies ran along parallel lines, and that those who were good at running a household were also good at running a public administration.

Giacomo Lanteri lived in the second half of the 16th century and was famous in his time as a mathematician and expert in military fortifications, on which he wrote several treatises. He was appointed chief engineer at the court of King Philip II and later transferred to Naples, where he died in 1560. According to other sources, Lanteri also occasionally served the Pope and the Republic of Venice (cf. V. Peroni, Biblioteca Bresciana, Brescia, 1823, II, pp. 170-171; see also G. Vivenza, Giacomo Lanteri da Paratico e il problema delle fortificazioni nel secolo XVI, in: "Economia e storia", October-December 1975, pp. 503-505).

Edit 16, CNCE45483; USTC, 837349.

Two works in one volume (143x98 mm). Later half vellum with lettering piece on spine. Small round worm holes to the inner margin of the first leaves, a few later marginal annotations in the first work, occasional pale foxing, upper margin cut a bit short, all in all a good copy.

Interesting Sammelband gathering two major Italian dialogues on domestic economy and household management, a genre which also includes education of children, women's role in the family, home architecture, and agriculture, and which was first started in the 16th century by the revival of Aristotle's Politics, Xenofon's Economics and, more recently, L.B. Alberti's treatise on family.

"In fact, the publication of Caggio's work in 1552 marked the beginning of the reworking of classical 'economics' into original writings in which tradition and innovation come together in a highly effective synthesis. The Iconomica of Paolo Caggio, born in Palermo, is a short dialogue between two characters, father and son, in which the former plays the role of 'tutor' for everything concerning family life. What is remarkable about this piece of writing is how the intention of the 'docere' (teaching) is accompanied by an articulation that is more discursive than normative, almost as if the author wanted to amuse and 'delight' his readers at the same time. The function of the dialogic genre thus becomes essential in order to escape the gravity of the classical-humanist 'institutio' in favour of a medium tone appropriate to family conversation. An educational work, then, and at the same time a 'family dialogue': under the banner of a literary rather than theoretical commitment, of an 'academic' rather than doctrinal effort. In fact, it is Caggio himself who, at the beginning of his work, addresses his readers in order to emphasise the pleasant and literary character of his work. Precisely because of its character as a common, everyday experience, we will see how the family is indeed suited to being the object of 'institution' and at the same time the subject of pleasant 'conversations', of learned or witty 'reasoning'. Also in dialogue form is the Economica that appeared a few years later by Giacomo Lanteri, in which the narrative is structured around the conversations that some Brescian 'gentlemen' entertain in the 'villa' of one of them. But despite this setting, the author immediately claims the character of necessary, useful and important knowledge to the subject he is about to treat: 'How much, most illustrious and excellent Madam, the science of economics, so celebrated by the ancient Greeks and Romans, has always been of great importance to human happiness, the rise and ruin of houses, which we see every day, can undoubtedly prove it. For many have raised their houses from the lowest to the highest degree by good government, and many others, by bad government, have plunged themselves and their heirs into great misery'. Thus begins the dedication of the work 'To the most illustrious and excellent lady, Madame Renata of France', and this concern of Lanteri's for the possible ruin of noble families fits well, as we shall see, with the attention he devotes in the work to the problems of wealth, trade and agriculture. A greater awareness, based on direct knowledge and personal experience, dominates Lanteri's writing compared to Caggio's earlier work. A lawyer and academic who never left the island, Caggio, who was born in Palermo, seems to have been mainly concerned with making his work conform to a literary model that was being imposed at the time, and even when he referes to the situation of his island, it is to cultural problems that he devotes most of his attention. There is no trace of this attitude in Lanteri. More open, more 'scientific', more 'technical, also thanks to his main occupation, in the treatise he establishes a constant comparison between the classical precepts of 'economy' and the situation of the Brescian reality of his time, aiming above all at the efficacy of his teachings and not at the form and elegance of the style. Both, however, choose as their mode of expression the 'dialogue', that is to say, a form of expression that does not claim to be the 'truth', but leaves room for replies, objections, divergent positions, even if these are then brought back into the main discourse by one of the characters, the author's direct spokesman. But, in short, we are not yet in the presence of a finished treatise, of a total 'institutio' free of doubt, such as we will find at the end of the century and the beginning of the 17th century. The re-proposal of the 'economic' in these early works is still open to the observation of reality and the perception of its contradictions, and is open to the most diverse positions. Of course, the author's pretension is never absent, and he never fails to give his opinion to one of the protagonists of the dialogue, who in the end represents the dominant opinion. In this way, the different positions that confront each other in the 'dialogue' end up producing a synthesis that is often identified with the communis opinio, with the norms accepted by all by tradition or conviction. Or, on the other hand, by 'experience': the presentation of 'economics' is then entrusted to a person who, by virtue of his age or way of life, presents himself as the main advocate of the need for domestic 'discipline' and as the guarantor of the validity of the norms as they are expressed" (D. Frigo, Il padre di famiglia. Governo della casa e governo civile nella tradizione dell' "economica" tra Cinque e Seicento, Rome, 1985, pp. 35-37, and ad indicem). (Inventory #: 222)

Rare first edition, edited by Girolamo Ferlito who signs the dedication to Bernardino Sanseverino, Duke of Somma, from Venice on 15 May 1522. The work was reprinted by Arravabene the following year.

Caggio's Iconomica is written in the form of a dialogue that takes place over the course of two days between two interlocutors, the aged and wise Apollonius and the young and impulsive Monophilus. In the form of benevolent instruction, Apollonius tries to persuade Monophilus of the need to form a family. To (truncated) this end, the author analyses a wide range of issues relating to family government, such as what the family is; the differences between the prince and the father of the family; the qualities and virtues required of a woman to be an excellent wife and mother (Caggio shows great respect and admiration for the female gender); the differences between the two sexes that make them complementary (Caggio advocates relationships between men and women characterised by mutual understanding and cooperation); the praise of marriage; the education of children (he also discusses the lack of good schools in the Kingdom of Sicily); the importance of cultivating good friendships; how to deal with servants; how to preserve and increase wealth; the value and development of agriculture; the duties of the father in order to make the family administration prosperous; and so on (cf. G. Ratto, Introduzione, in: P. Caggio, "Iconomica", Naples, 1986, pp. 11-82).

Paolo Caggio was born in Palermo around 1525 into a wealthy family of senators. He studied law and held several public offices during his career, including the post of secretary or chancellor of the senate. He apparently never left Sicily during his lifetime. The publication in Venice of his works (Ragionamenti, 1551; Flamminia prudente, 1551; and Iconomica, 1552) was undertaken by his friend Ottaviano Precone, Bishop of Monopoli. In 1549 Caggio founded the Accademia dei Solitari to promote the spread of the Italian language in Sicily through the study of the works of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio.

"The play (Flamminia prudente, Venice 1551) is thus to some extent the 'female' counterpart to Caggio's Iconomica, in which male speakers discuss male prudentia and which was aimed at an educated and thus predominantly male audience. Against this background, the choice of genre also appears to be gendered: the dialogue (Iconomica) is addressed to male recipients, the entertaining and educational play (Flamminia prudente) to a mixed audience - although in the latter case the economic-didactic part is explicitly addressed to female viewers, whereas the literary satire is presumably addressed primarily to a male audience (and especially to scholars). This can be explained not least by the fact that, compared to the theoretical discourse, the theatrical performance reaches a potentially wider circle of female recipients, namely those women who have little literary education or are illiterate. Especially in its final form, the performance of the drama also has a liveliness that treatises and dialogues, because of their written form, cannot achieve. In addition to this, catchy linguistic register, brevity and entertainment enable a comedy such as the Flamminia prudente to appeal to a completely different audience than the theoretical genres" (Ch. Schaefer, Weibliche "prudentia" auf der Bühne. Zur Inszenierung ökonomischer Konzepte in Paolo Caggios "Flamminiaprudente" (1551), in: "Das Haus Schreiben. Bewegungen ökonomischen Wissens in der Literatur der Frühen Neuzeit", Ch. Schaefer & S. Zeisberg, eds., Wiesbaden, 2018, pp. 145-146).

Edit 16, CNCE8270; USTC, 817608.

(bound with:)

LANTERI, Giacomo (d. 1560). Della economica trattato di M. Giacomo Lanteri gentilhuomo bresciano nel quale si dimostrano le qualità, che all'huomo et alla donna separatamente convengono pel governo della casa. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1560.

8vo. [32], 171, [5] pp. Collation: *-**8 A-L8. The last leaf is a blank. Printer's device on the title page and on l. L7v. Errata at l. L6v. Woodcut historiated initials. Roman and italic type.

Rare first edition, dedicated by Lanteri to Renée of France, Duchess of Ferrara.

According to Lanteri, the "economica" or household economy is a science whose importance and necessity is demonstrated by the ruinous fortunes of so many families over the years. Lanteri, an expert in military architecture, describes the characteristics of the family home according to social status, from the noble to the merchant; he also discusses at length the different roles of father and mother, the choice of servants and the education of children. As for the actual economy, while Lanteri does not consider it disreputable for the pater familias to engage in commerce, he considers agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting to be the most noble and appropriate activities for him. Like Caggio, Lanteri also believed that the domestic and public economies ran along parallel lines, and that those who were good at running a household were also good at running a public administration.

Giacomo Lanteri lived in the second half of the 16th century and was famous in his time as a mathematician and expert in military fortifications, on which he wrote several treatises. He was appointed chief engineer at the court of King Philip II and later transferred to Naples, where he died in 1560. According to other sources, Lanteri also occasionally served the Pope and the Republic of Venice (cf. V. Peroni, Biblioteca Bresciana, Brescia, 1823, II, pp. 170-171; see also G. Vivenza, Giacomo Lanteri da Paratico e il problema delle fortificazioni nel secolo XVI, in: "Economia e storia", October-December 1975, pp. 503-505).

Edit 16, CNCE45483; USTC, 837349.

Two works in one volume (143x98 mm). Later half vellum with lettering piece on spine. Small round worm holes to the inner margin of the first leaves, a few later marginal annotations in the first work, occasional pale foxing, upper margin cut a bit short, all in all a good copy.

Interesting Sammelband gathering two major Italian dialogues on domestic economy and household management, a genre which also includes education of children, women's role in the family, home architecture, and agriculture, and which was first started in the 16th century by the revival of Aristotle's Politics, Xenofon's Economics and, more recently, L.B. Alberti's treatise on family.

"In fact, the publication of Caggio's work in 1552 marked the beginning of the reworking of classical 'economics' into original writings in which tradition and innovation come together in a highly effective synthesis. The Iconomica of Paolo Caggio, born in Palermo, is a short dialogue between two characters, father and son, in which the former plays the role of 'tutor' for everything concerning family life. What is remarkable about this piece of writing is how the intention of the 'docere' (teaching) is accompanied by an articulation that is more discursive than normative, almost as if the author wanted to amuse and 'delight' his readers at the same time. The function of the dialogic genre thus becomes essential in order to escape the gravity of the classical-humanist 'institutio' in favour of a medium tone appropriate to family conversation. An educational work, then, and at the same time a 'family dialogue': under the banner of a literary rather than theoretical commitment, of an 'academic' rather than doctrinal effort. In fact, it is Caggio himself who, at the beginning of his work, addresses his readers in order to emphasise the pleasant and literary character of his work. Precisely because of its character as a common, everyday experience, we will see how the family is indeed suited to being the object of 'institution' and at the same time the subject of pleasant 'conversations', of learned or witty 'reasoning'. Also in dialogue form is the Economica that appeared a few years later by Giacomo Lanteri, in which the narrative is structured around the conversations that some Brescian 'gentlemen' entertain in the 'villa' of one of them. But despite this setting, the author immediately claims the character of necessary, useful and important knowledge to the subject he is about to treat: 'How much, most illustrious and excellent Madam, the science of economics, so celebrated by the ancient Greeks and Romans, has always been of great importance to human happiness, the rise and ruin of houses, which we see every day, can undoubtedly prove it. For many have raised their houses from the lowest to the highest degree by good government, and many others, by bad government, have plunged themselves and their heirs into great misery'. Thus begins the dedication of the work 'To the most illustrious and excellent lady, Madame Renata of France', and this concern of Lanteri's for the possible ruin of noble families fits well, as we shall see, with the attention he devotes in the work to the problems of wealth, trade and agriculture. A greater awareness, based on direct knowledge and personal experience, dominates Lanteri's writing compared to Caggio's earlier work. A lawyer and academic who never left the island, Caggio, who was born in Palermo, seems to have been mainly concerned with making his work conform to a literary model that was being imposed at the time, and even when he referes to the situation of his island, it is to cultural problems that he devotes most of his attention. There is no trace of this attitude in Lanteri. More open, more 'scientific', more 'technical, also thanks to his main occupation, in the treatise he establishes a constant comparison between the classical precepts of 'economy' and the situation of the Brescian reality of his time, aiming above all at the efficacy of his teachings and not at the form and elegance of the style. Both, however, choose as their mode of expression the 'dialogue', that is to say, a form of expression that does not claim to be the 'truth', but leaves room for replies, objections, divergent positions, even if these are then brought back into the main discourse by one of the characters, the author's direct spokesman. But, in short, we are not yet in the presence of a finished treatise, of a total 'institutio' free of doubt, such as we will find at the end of the century and the beginning of the 17th century. The re-proposal of the 'economic' in these early works is still open to the observation of reality and the perception of its contradictions, and is open to the most diverse positions. Of course, the author's pretension is never absent, and he never fails to give his opinion to one of the protagonists of the dialogue, who in the end represents the dominant opinion. In this way, the different positions that confront each other in the 'dialogue' end up producing a synthesis that is often identified with the communis opinio, with the norms accepted by all by tradition or conviction. Or, on the other hand, by 'experience': the presentation of 'economics' is then entrusted to a person who, by virtue of his age or way of life, presents himself as the main advocate of the need for domestic 'discipline' and as the guarantor of the validity of the norms as they are expressed" (D. Frigo, Il padre di famiglia. Governo della casa e governo civile nella tradizione dell' "economica" tra Cinque e Seicento, Rome, 1985, pp. 35-37, and ad indicem). (Inventory #: 222)

![Publii Virgilii Maronis Opera, cum Servii commentariis, exactiori cura suae integritati restitutis. Habes item Io. Pierii Valeriani Castigationes, & Verietates lectionis in totum Virgilium […] Accedunt praeterea in omnia Virgili opera Stephani Doleti Annotatiunculae, Ioca obscura elucidantes, ac doctissimi Commentarii vicem fingentes. Additis novis quibusdam Io. Musonii viri quam eruditissimi lucubrationibus, quas inspexisse haud quaquam pigebit: [...]](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/001/648/1692648001.0.m.jpg)

![Theatrum machinarum novum, exhibens aquarias, alatas, iumentarias, manuarias; pedibus, ac ponderibus versatiles, plures, et diversas molas [...] Per Georgium Andream Bocklerum, architectum & ingeniarum. Ex Germania in Latium recens translatum opera R.D. Henrici Schmitz, [...]](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/985/647/1692647985.0.m.jpg)