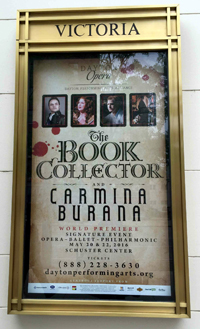

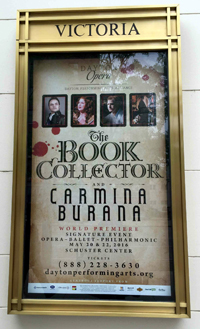

Friday, May 20th will see the premiere of my new opera with composer Stella Sung, a “rare book” opera, if you will, called The Book Collector, in which two men vie for possession of an exceedingly rare book.

Why a rare book opera, you may ask?

In truth, the opera is driven by the forces that have defined opera since its earliest days: jealousy and love, vengeance and mercy, the clash of social classes, free will bound by fate, and tragic, sometimes deadly misunderstandings. The auction floor, the bookseller’s shop, the private library, and the book itself really serve as settings and props for the larger human ambitions that animate the characters. The “rare book” aspect of the opera was Stella’s. She’s long been fascinated by my day job at Bauman Rare Books. In fact, the first time we met in person was at the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair, the Florida Antiquarian Booksellers' Association's show held in St. Petersburg’s Historic Coliseum (my friend Dana Gioia, former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, first introduced the two of us as collaborative partners, but our work up to that point was done long-distance).

In truth, the opera is driven by the forces that have defined opera since its earliest days: jealousy and love, vengeance and mercy, the clash of social classes, free will bound by fate, and tragic, sometimes deadly misunderstandings. The auction floor, the bookseller’s shop, the private library, and the book itself really serve as settings and props for the larger human ambitions that animate the characters. The “rare book” aspect of the opera was Stella’s. She’s long been fascinated by my day job at Bauman Rare Books. In fact, the first time we met in person was at the Florida Antiquarian Book Fair, the Florida Antiquarian Booksellers' Association's show held in St. Petersburg’s Historic Coliseum (my friend Dana Gioia, former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts, first introduced the two of us as collaborative partners, but our work up to that point was done long-distance).

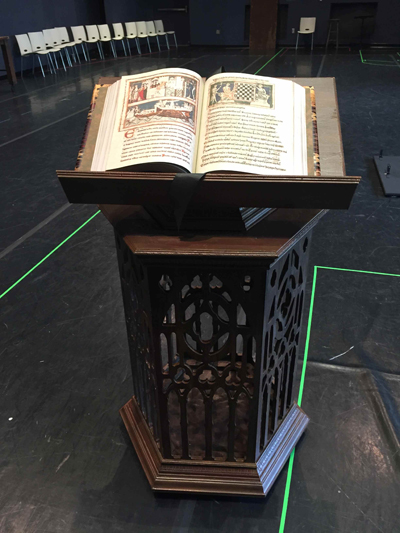

Before we began work on The Book Collector, I had already worked with Stella as a librettist but, as the Dayton Daily News explains, my background situated me ideally—as both librettist and rare book dealer, perhaps a unique combination—“to fashion a plausible scenario for this particular opera.” Having worked at Bauman Rare Books for nearly a decade and a half, I understand the physical properties of books as well as the ways in which they are created and go on to change hands over the centuries. I was able to provide extensive descriptive information and provide visual examples of books and their settings for both physical and virtual design staffs.

I have considerable experience bidding for books at auction houses, so I am familiar with the showroom, its practices and idiosyncrasies. The auction house is really an 18th-century form of commerce, and much of the language and practices from that era persist down to the present day. I envisioned the auction that begins the opera as a duel between two strong-willed men. Bidding at auction can quickly become an irrational pursuit, as egos and expectations tangle and adrenaline flows.

Commissioned by Dayton Performing Arts Alliance in 2013 as a prologue to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, which Sung is directing, Sung’s opera The Book Collector is a one-act Gothic tale of what we call “unforeseen fortunes and ancestral madness, young love and powerful obsession,” played out against the backdrop of the Bavarian city of Bamberg—known across Europe as the “Franconian Rome” for its seven hills, each crowned with a beautiful church—at the start of the nineteenth century. The dashing and impulsive Baron Otto von Schott, long a recluse in his fortress, hopes to finally complete his collection of arcane books with the addition of a final mysterious volume, but he finds himself thwarted by Franz Bierman, a shrewd young bookseller. The enraged Baron plots revenge, ultimately entangling his lonely, unsuspecting daughter Anna in his deranged scheme to retrieve the book from the bookseller. Franz and Anna find themselves falling in love, and, after the unexpected intercession of a noiseless, enigmatic monk, the Baron’s madness deepens until it is finally too late for him to turn away from his own fate.

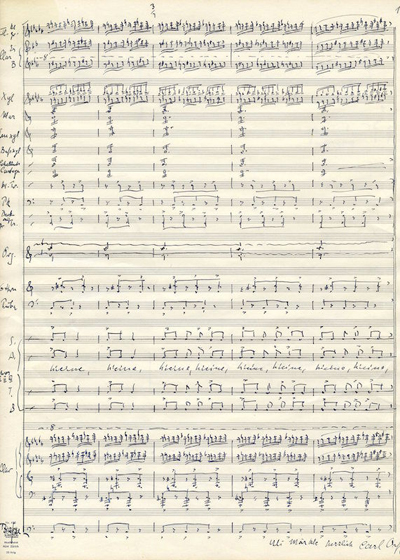

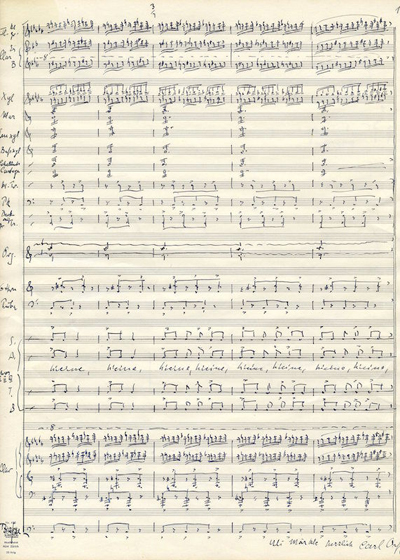

Autograph musical manuscript signed of De temporum fine comoedia. Das Spiel vom Ende der Zeiten. Undated, but ca. 1970

De temporum fine comoedia (Play for the End of Time), a major work, was Orff's final musical statement. It was composed over a period of some ten years and had its first performance on August 20, 1973 at the Salzburg Music Festival under Herbert von Karajan with the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra. Large folio (416 x 318 mm.). Notated in ink and pencil on 30-stave music manuscript paper. Inscribed to Uli Märkle, a close collaborator and friend of the distinguished Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan. ��(Offered by J. & J. Lubrano Music Antiquarians)

The opera, which combines physical stage sets with virtual 3D digital sets, also includes a full ballet sequence. The project was funded in part by the League of American Orchestras, New Music USA, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, and the ASCAP Foundation.

Of course, the city of Dayton is not unfamiliar with the world of rare books. As Nicholas A. Basbanes reported in Fine Books and Collections, collector Stuart Rose loaned fifty volumes from his famous two-thousand-volume library for an exhibition called “Imprints and Impressions: Milestones in Human Progress” at the University of Dayton last year. Mr. Rose displayed interest in our opera from the start and donated generously toward the production.

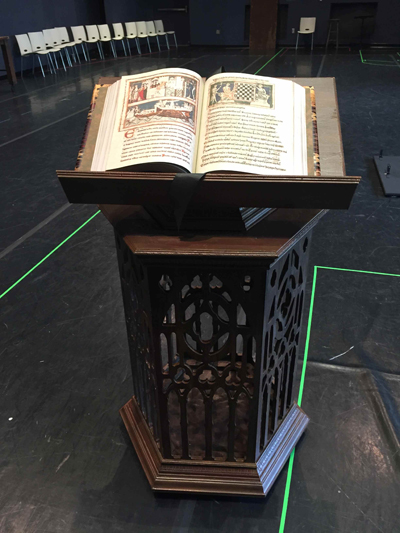

For the Dayton premiere, celebrated baritone Andrew Garland will assume the role of the villainous Baron Otto von Schott. Soprano Angela Mortellaro, who in starred in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor during the Dayton Opera’s 2012 season, will be our Anna. Tenor Andrew Owens portrays Franz Bierman, the wealthy bookseller who sparks a feud by outbidding the Baron for the prized volume at auction. We added non-singing roles to fill out the action, notably the auctioneer (who is heard but who does not sing, performed by professional auctioneer Tim Lile) and the monk, who is entirely silent and serves as a Rorschach test when addressed by the other characters. At first, I planned to have the baron bid on a dozen quarto volumes at auction. These quickly shrank to become a single volume, which, for the sake of dramatic impact, was enlarged to an imperial folio with elaborate clasps and binding in order to register visually on stage.

Stella had a distinct vision for the opera from the first. The story is hers, and it was fully realized before she began work with me. My job, as librettist, was to broaden her story and deepen the characters by giving them the right words to sing. The baron’s impulsive nature would be brought to the fore through his curses and frenzied outbursts. His growing madness would be summoned by his fanatical repetition of certain phrases. Anna is innocent and inquisitive. This is reflected in her frequent use of the interrogative mood. Many of her lines are questions, far more than either of the other characters. She is in love with the world and wants to know more about it. Bierman’s fundamental decency and eagerness is displayed in his propensity to over-explain the simplest things in his efforts to please and impress the other characters.

I was also compelled by thoughts of characters that were, by their very nature, absent. I saw the baron’s mania for filling his library as part of an emotional aftershock from the loss of his wife. In other words, though he assumes the role of villain in this opera, he was not always an angry, arrogant recluse. Her death also compels Anna to assume the role of the baron’s caretaker in her absence, thus trapping her in the home. Further, Bierman was not always driven by thoughts of profit and public advancement. In early drafts of the libretto, he too had lost someone he loved and, like the baron, looked for ways to fill the emptiness in his life.

I was also compelled by thoughts of characters that were, by their very nature, absent. I saw the baron’s mania for filling his library as part of an emotional aftershock from the loss of his wife. In other words, though he assumes the role of villain in this opera, he was not always an angry, arrogant recluse. Her death also compels Anna to assume the role of the baron’s caretaker in her absence, thus trapping her in the home. Further, Bierman was not always driven by thoughts of profit and public advancement. In early drafts of the libretto, he too had lost someone he loved and, like the baron, looked for ways to fill the emptiness in his life.

I further sought to strengthen and emphasize the social and historical distinctions among the characters. The baron broods in his ancestral fortress, cluttered with the acquisitions of centuries, his library ill-lit, representative of a dark, aristocratic past of which he is the latest and perhaps last representative. Bierman exists in a world naturally lit by sunlight, his bookstore exceptionally ordered, a member of a rising middle class and part of an enlightened and more democratic age of commerce and shared knowledge. I took care to point out that the baron drinks wine, while Bierman, as his name would suggest, enjoys beer, a drink more common in the lower echelons of Teutonic society. The baron—born to inherited wealth he squanders and noble privilege that is quickly eroding—is in decline. Bierman is a commoner, but he rises. Anna is pulled between these two worlds, devastated by the weight of the first while daydreaming of escape into the second. What drives the baron? How has he focused his frustration in a world that no longer bows before him? He aims his emotional distress onto the acquisition of a book; not any book, but the single book he has convinced himself will complete his collection (though we sense that nothing could really fulfill this goal).

Stella and I decided to imagine the baron questing after a single volume that would complete his set of the Carmina Burana. The extraordinary rarity and desirability of a single book is a very real thing. Consider Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, the monumental 1623 volume commonly known as the First Folio, in which Shakespeare’s plays were collected for the first time seven years after his death, and including first appearances of many of the plays, such as Macbeth. Depending on condition and provenance, copies of the First Folio can achieve many millions of dollars on the rare occasion that one comes onto the auction block. Just last month, a copy was found forgotten on a shelf where it had lain for over a century in a house on the Scottish Isle of Bute. The discovery made news around the world.

The Carmina Burana (or Codex Buranas, literally the “Songs from Beuern,” the Bavarian district where the manuscripts were discovered), is a series of 254 poems written in Medieval Latin, Middle High German, and a few mongrel mixtures from the vernacular of several other languages. The poems include love songs, drinking and gaming ditties, moral and satirical poems, and religious dramas. Our notion of the baron having assembled many volumes of the poems and seeking to acquire the last is not far-fetched. Historically, it is quite possible that someone could have done so. Little is known of the origins or authorship of the Carmina, though it is likely that the manuscripts were written sometime in the early 13th century in Bavaria. The history of the manuscript after the middle of that century is murky. Scholar David Parlett suggests that “by the eighteenth century the manuscript must have presented a sadly dog-eared appearance, for it is then that it received its leather binding.” The tooling on the leather indicates that the binding was probably done at the monastery of Benedikbeuern.

What we do know is that after an 1803 decree secularizing ecclesiastical property in the region the volumes emerged from an uncatalogued library at the monastery, where they were kept away from other books in the official library, in what Parlett suggests may have been a type of index librorum prohibitorum of heretical writings. In other words, these volumes were not like the others the monks would have consulted or made available to outsiders. The first publication of the manuscripts would not come until 1847, when the collection was given its current title by its editor, Johann Andreas Schmeller, who had removed the volumes to Munich for cataloging. Just as Stella and I filled in the emotional spaces of the characters with words and music, we filled a historical gap by imagining the tortuous route by which the Carmina volumes came to rest in the monastery. This also enabled me to take the poems in the original Carmina Burana as models for the arias. The forms of the poems gave me license to write in verse, an artistic approach to the libretto that has fallen away since the nineteenth century and is now almost entirely extinct.

I employed a combination of verse-craft and traditional prose dialogue to propel Stella’s story, all the while posing and upending questions that vex characters across the history of literature and opera. How do the forces of fate and free will, circumstance and freedom, destiny and choice collide to create us? Where do our decisions lead, and how can we know they are entirely our own? What happens when we move headlong at all costs toward a goal we believe will make us happy? What do we lose by striving to remain independent? What do we risk when we place ourselves in the hands of another? These are the timeless themes Stella and I engage repeatedly in our work.

And so here we are, only a few days before the curtain rises on our “rare book” opera, after countless hours of composition and revision, construction and coding, preparations and rehearsals. This Friday, we will all witness a new opera for the first time, one that was forged with modern technology and artistic sensibilities to be part of an ancient tradition. We hope the stories and songs we conjure in the world of The Book Collector delight you and prove a memorable experience, even, perhaps—who knows?—one for the ages.

---

For more information about The Book Collector, visit the Dayton Performing Arts Alliance.

In truth, the opera is driven by the forces that have defined opera since its earliest days: jealousy and love, vengeance and mercy, the clash of social classes, free will bound by fate, and tragic, sometimes deadly misunderstandings. The auction floor, the bookseller’s shop, the private library, and the book itself really serve as settings and props for the larger human ambitions that animate the characters. The “rare book” aspect of the opera was Stella’s. She’s long been fascinated by my day job at Bauman Rare Books. In fact, the first time we met in person was at the

In truth, the opera is driven by the forces that have defined opera since its earliest days: jealousy and love, vengeance and mercy, the clash of social classes, free will bound by fate, and tragic, sometimes deadly misunderstandings. The auction floor, the bookseller’s shop, the private library, and the book itself really serve as settings and props for the larger human ambitions that animate the characters. The “rare book” aspect of the opera was Stella’s. She’s long been fascinated by my day job at Bauman Rare Books. In fact, the first time we met in person was at the

I was also compelled by thoughts of characters that were, by their very nature, absent. I saw the baron’s mania for filling his library as part of an emotional aftershock from the loss of his wife. In other words, though he assumes the role of villain in this opera, he was not always an angry, arrogant recluse. Her death also compels Anna to assume the role of the baron’s caretaker in her absence, thus trapping her in the home. Further, Bierman was not always driven by thoughts of profit and public advancement. In early drafts of the libretto, he too had lost someone he loved and, like the baron, looked for ways to fill the emptiness in his life.

I was also compelled by thoughts of characters that were, by their very nature, absent. I saw the baron’s mania for filling his library as part of an emotional aftershock from the loss of his wife. In other words, though he assumes the role of villain in this opera, he was not always an angry, arrogant recluse. Her death also compels Anna to assume the role of the baron’s caretaker in her absence, thus trapping her in the home. Further, Bierman was not always driven by thoughts of profit and public advancement. In early drafts of the libretto, he too had lost someone he loved and, like the baron, looked for ways to fill the emptiness in his life.