Description & Display Recommendations from the ABAA Diversity Initiative

The aim of this document is to suggest some “best practices” for ABAA members in cataloguing and selling culturally sensitive material.

The recommendations have been composed in the spirit of continuing education, drawing together input from fellow members, scholars, and librarians. Its authors will continue to seek advice from the rare book community, particularly from those who are members of marginalized or oppressed groups. It is meant to be an evolving resource, adapting over time to the many ways we find ourselves facing the complex issues encountered when handling sensitive material. It makes no pretense at being the final authority on these issues, nor is it comprehensive in its scope. Insofar as it makes any claims, it is that engaging with culturally sensitive material in such a way that ensures the dignity of the community or communities involved is necessary, important work, and that we will all be better cataloguers for doing it.

We particularly address materials related to historically marginalized and oppressed communities. Some (but certainly not all) of these groups include:

- Women

- People with disabilities

- Black people, Indigenous people, and those who identify as people of color (sometimes referred to as BIPOC, although this is a contentious term)

- People of Latin American origin or descent (sometimes termed Latinx, a gender-neutral from of Latino and Latina)

- Asian people and Pacific Islanders (AAPI)

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) people

As purveyors of such material, booksellers play a unique and sometimes fraught role: we are both purchasers and sellers, tasked at both ends of the transaction with being the public face of the market for this material and therefore responsible for handling it in a way that is respectful to our customers and to the material itself. Learning to catalogue and present this material as accurately and professionally as possible is an ongoing process, requiring us to educate ourselves and our staffs on the most updated terminology, to be open to suggestions from members of the communities the material represents, and to question our own assumptions and unconscious biases. It is, in other words, work, but it is not the kind of work any of us is a stranger to. We do it all the time, whenever we encounter any material outside the range of our personal experience, knowledge, and comfort level.

By considering diverse perspectives and using thoughtful language and illustrations when cataloguing and marketing rare materials, members will help further the ABAA’s goal to provide a welcoming and equitable space for a rising generation of sellers, collectors, and librarians. Understanding how we and our materials impact others is both a responsibility and an opportunity for the growth of the book trade – and, potentially, the growth of our own businesses, as well. By presenting ourselves and our material as respectfully as possible, we have the chance to better connect with collectors and curators, and to burnish our reputations for accuracy and scholarship.

Recognizing the Audience: By, For, and About

By providing proper context for culturally sensitive materials and considering how their presentation guides the way they are received, cataloguers can help readers/viewers understand if the material is By, For, or About a community. Broadly speaking, these categories refer to: 1) who the author or creator of the material is; 2) who the intended audience is; and 3) what community the material is about.

For example, let’s look at Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo and her other, similar books. Long considered classic children’s literature in the Western canon and described as “Black Americana” by many in the trade since their publication, who are these books By, For, and About? Well, the books are by Helen Brodie Cowan Bannerman (1862-1946), a white Scottish woman, and, although all the books are ostensibly about Black characters, they rely on what have become recognized as racist tropes and racist caricature, meant, in fact, for a white audience, not a Black one.

So, what does this mean? For starters, it means that neither the author nor the audience belong to the community being (mis)described, and that affects how sellers characterize what the material is. Rather than calling it “Black Americana” – it is not describing Black people accurately, nor even with good intention, and although it draws on similar sources as those used in some Black American folktales, all of Bannerman’s stories are set in India – booksellers must find a more accurate term or terms.

As another overt example, let’s take The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which the Holocaust Encyclopedia notes is “the most widely distributed antisemitic publication of modern times.” Should it be considered Judaica? Well, it is ostensibly about Jewish people, but it was written for an audience who would agree with its antisemitic message – that is, not only a non-Jewish audience but one seeking to validate its hatred of Jewish people. Calling this Judaica is therefore problematic and deserving of greater consideration on the part of the bookseller.

What terms do we use, then – especially when we are likely working within the constraints of the broad categories in our databases and on our websites? How do we acknowledge the sensitive and/or problematic nature of the material while still promoting its desirability to potential buyers, and doing so with the assumption that our customers may come from all walks of life – including from the community or communities being demeaned, disparaged, etc., by the material?

Bracketing and Descriptors

One way to do this is through bracketing and descriptors placed at the beginning of a catalogue description. These can indicate from the outset whether the material is by, for, or about a community. If the author identifies as LGBTQ+, for example, you could use [LGBTQ+ Authorship]; if the material is promoting the Black community, [Black Activism] might be applicable; and if the material is about a scientist who is a woman, [Women in STEM] might work. As you’ll note, all of these examples allow broad categories like [LGBTQ+], [Black/ African American], and [Women] to become more precise, and thus to more accurately describe the material.

Bracketing can also be used to assist us and our readers by foregrounding the problematic, violent, or demeaning nature of certain material, such as Little Black Sambo or The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. It can allow us to acknowledge that the content was made about a group without their involvement and possibly to their detriment. Some examples include:

- [Anti-Suffrage]

- [Sexual Violence]

- [Racist Caricature]

- [Lynching]

- [Antisemitism]

- [Anti-Immigrant Propaganda]

- [Homophobia]

Keep in mind that these categories do not have to stand alone. One way to handle Little Black Sambo, for instance, might be to use [Children’s Literature] and [Racist Caricature] together, thereby allowing us to acknowledge both the book’s historical designation as being “classic children’s literature” and its demeaning portrayal of its Black protagonist.

Another way we may wish to combat overly broad categorization on our websites, at least, is the use of subcategories. Many website platforms allow for the “nesting” of categories, so that, for example, “Antisemitism” could be a subcategory of “Judaica.” Obviously, such nesting of categories still requires forethought and consideration, but may allow customers to locate the material they’re looking for more easily – without having to wade through material they don’t wish to see, or, worse, thinking a bookseller doesn’t know the difference between the categories.

Introductions, Images and Displays

Some material may also warrant an introductory text, beyond what can be accomplished with bracketed categories. Even when material containing these images is thoughtfully catalogued, graphic displays can have a swift and visceral impact on a potential customer. We recommend that members be mindful of customers’ possible reactions to the central or prominent placement of images that are de-humanizing, racist, sexist, homophobic, or violent, whether in catalogues, on our websites, or displayed in our booths at book fairs.

Please note: we are not suggesting such material not be offered at all. Rather, as with our textual descriptions, contextualization is key for visual displays. Some ways to contextualize visual displays at book fairs include:

- Ensuring that our descriptions of problematic material are at least as readily visible as the material itself, so that viewers can turn immediately to them for reference.

- Shelving problematic or sensitive material together, in a less prominent position than material by or for a traditionally underrepresented group, for example, shelving racist material separately from African American material, perhaps nearby but on a different shelf.

- Also displaying material that critiques or broadens the conversation about the problematic material, such as American Indian Movement posters in addition to caricatured images of Indigenous Americans.

One other aspect of visual displays is understanding how our specialties and reputation influence the expectations of customers walking into our booths – in other words, how we ourselves contextualize problematic material. A specialist in radical material, for instance, who has posters from a broad range of social movements displayed in their booth as well as material denouncing those movements and the groups of people spearheading them, will engender different expectations from customers than a specialist in pre-18th century English literature. Thus, it will require more tact and forethought for the specialist in English literature to display – not to mention sell! – problematic material from the 20th century.

And selling the material is ultimately the point. Contextualizing it properly, in our descriptions and displays, allows us to create and manage expectations, to acknowledge the variety of people that may be shopping, and to adroitly draw in customers to our booths and websites.

Asking the Right Questions

Beyond cataloguing, categorizing material as by, for or about different communities can help us to connect with collectors more effectively. When someone mentions interest in a field such as African Americana, for example, we can follow up with questions to better understand. For example:

- Are they collecting materials that are broadly by, for, or about African American individuals or communities?

- Are they specifically focused on Black authors or activists?

- Are they interested more broadly in empowering as well as oppressive parts of Black history?

- Are they collecting images of Black Americans produced for white audiences?

- How can we offer material that fits within and respects their collection’s parameters?

Ultimately, all of us want to understand our customers’ collecting focuses as best as possible, and to then be able to cater to their interests. Asking the right questions and employing our categorization in such a way that racist caricatures and memoirs of Black experience, for example, are understood by all parties as belonging to distinctly separate categories, allows us forge stronger and more fruitful connections with customers.

Differentiating Identity from Circumstances

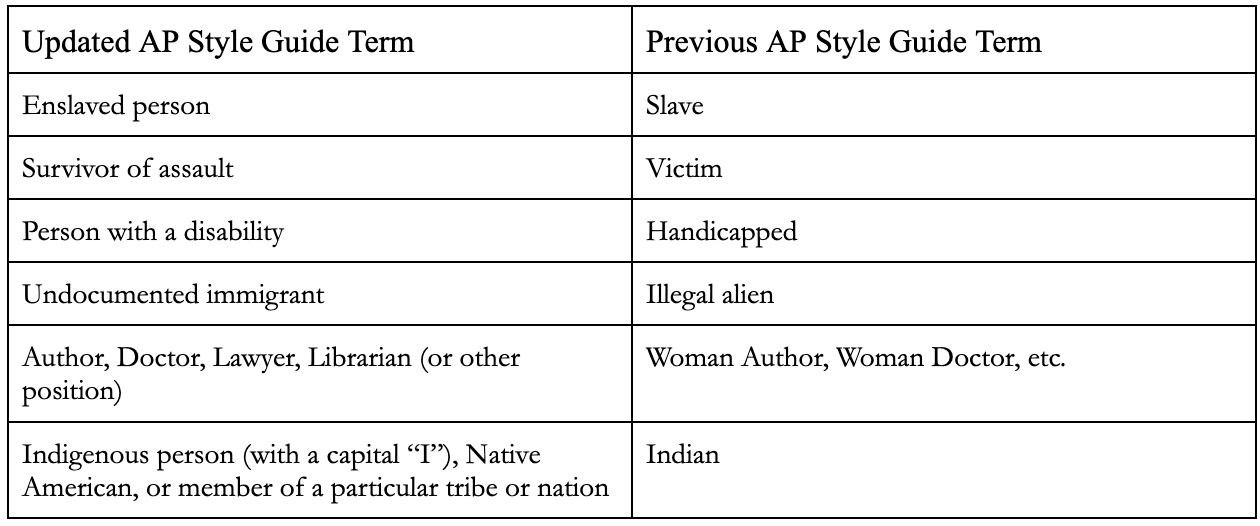

Terminology constantly changes and using the most up-to-date language is crucial when wishing to represent ourselves and our material as accurately and respectfully as possible. The AP amended its style guide in 2020 to include many changes of terminology (https://aceseditors.org/news/2021/ap-stylebook-updates-race-related-terms), particularly regarding “enslaved” and “Indigenous,” and other journalism guides address these changes as well (see Resources, below). One significant change in terminology in recent years has been to separate people’s identity from the circumstances that have been imposed upon them. For example:

It is important to recognize that no single term will be agreed upon by all members of a community: no identity group is a monolith, and people can identify as belonging to multiple groups. Moreover, just like terminology, communities are not static.

One prime example of this is how Indigenous Americans prefer to be addressed. Although “Indian” originated as a misnomer used by white settlers, some Indigenous Americans preferred the usage of “American Indian” during the Red Power Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, and some still prefer for that term to be used. Others, as noted above, prefer Native American as a broad term. Regardless, we suggest using the names of particular tribes or nations whenever possible.

Changing terminology can also be applied regarding white European narratives of exploration, for instance. Traditionally, these have been categorized as “Discovery and Exploration,” or referred to as “narratives of discovery.” However, “discovery” has become a contentious term in some circles. The most obvious reason for this is that lands previously unknown to Europeans were already inhabited by cultures that often suffered greatly from "discovery.” Consequently, 21st century booksellers need to be aware that “discovery” can be seen as problematic; one possible alternative is simply categorizing the material as “Exploration,” or being more specific and referring to it as “European Exploration” or “European Colonization.”

It is possible to describe how something fit into the social values of its time, without resorting to apologetics. Stating that racist material relating to African American experience was acceptable “for its time” may overlook contemporaries who actively protested, resisted, or sought change. For example, although Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind was a literary darling in mainstream media when it was published, it was also criticized immediately in some sectors of the Black press. When presenting the historical context of such material, we have a responsibility not to limit that context to favorable views, and to explain how the material’s reception has changed over time.

We bring our own experiences and histories to bear every time we describe a book, pamphlet, archive, or scrap of ephemera. We also change over time, just as culture and accepted terminologies shift over time. For this reason, revisiting and revising descriptions of older inventory can be valuable, and may even bring new marketability and relevance to the material we offer for sale.

Additional Resources for Description & Display from the ABAA Diversity Initiatve