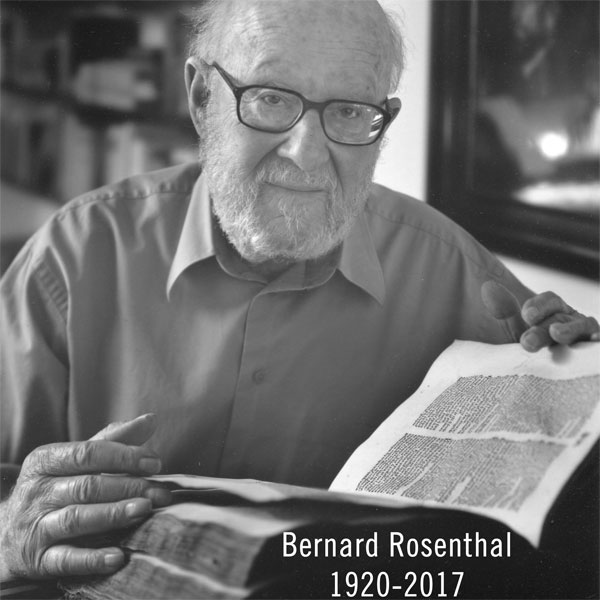

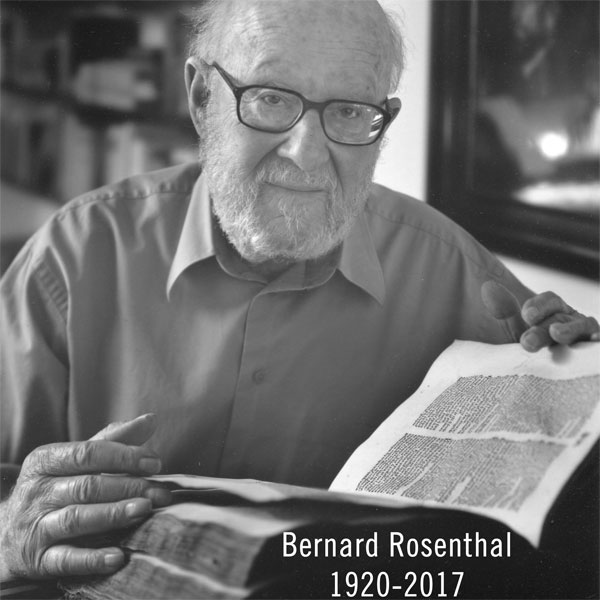

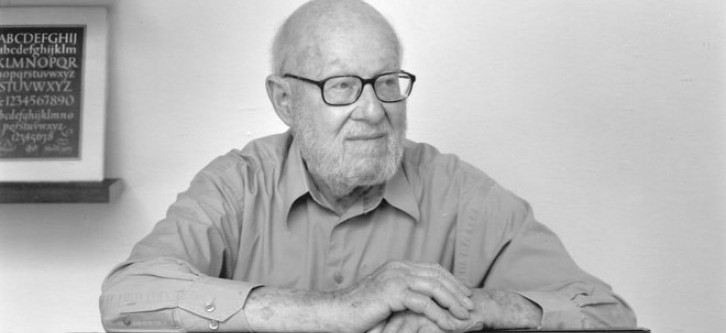

Bernard M. Rosenthal was born in 1920 in Munich. Most of his immediate family left Munich for Florence in 1933, left Italy for France in 1938, and arrived in the US in 1939, each move in response to the problem of being Jewish. Both sides of his family, the Rosenthals and on his mother’s side, the Olschkis of Italy, were heavily involved in the book trade going back generations as antiquarians, printers, publishers and authors. An extensive interview with Rosenthal was conducted by Dan Slive (head of Special Collections of the Bridwell Library at SMU) and appeared in the RBM Journal in 2003; in it, Rosenthal gives a fulsome account of his early days in the trade, starting in 1949 as an apprentice bookseller in Zurich under a bibliographical “tyrant,” Herr Frauendorfer, then later under the tutelage of Arthur Swann at Parke-Bernet, and finally starting off on his own in 1953, at 71st and Madison in Manhattan as a seller of scholarly and bibliographical works. In 1970 he moved his firm to San Francisco and remained in Northern California the rest of his life. His specialties included early printed and manuscript books, the history of scholarship and bibliography, and paleography. He joined the ABAA in 1955, served as its president from 1968-70, and was a generous guide, resource and mentor to many of the ABAA’s current members.

Bernard M. Rosenthal was born in 1920 in Munich. Most of his immediate family left Munich for Florence in 1933, left Italy for France in 1938, and arrived in the US in 1939, each move in response to the problem of being Jewish. Both sides of his family, the Rosenthals and on his mother’s side, the Olschkis of Italy, were heavily involved in the book trade going back generations as antiquarians, printers, publishers and authors. An extensive interview with Rosenthal was conducted by Dan Slive (head of Special Collections of the Bridwell Library at SMU) and appeared in the RBM Journal in 2003; in it, Rosenthal gives a fulsome account of his early days in the trade, starting in 1949 as an apprentice bookseller in Zurich under a bibliographical “tyrant,” Herr Frauendorfer, then later under the tutelage of Arthur Swann at Parke-Bernet, and finally starting off on his own in 1953, at 71st and Madison in Manhattan as a seller of scholarly and bibliographical works. In 1970 he moved his firm to San Francisco and remained in Northern California the rest of his life. His specialties included early printed and manuscript books, the history of scholarship and bibliography, and paleography. He joined the ABAA in 1955, served as its president from 1968-70, and was a generous guide, resource and mentor to many of the ABAA’s current members.

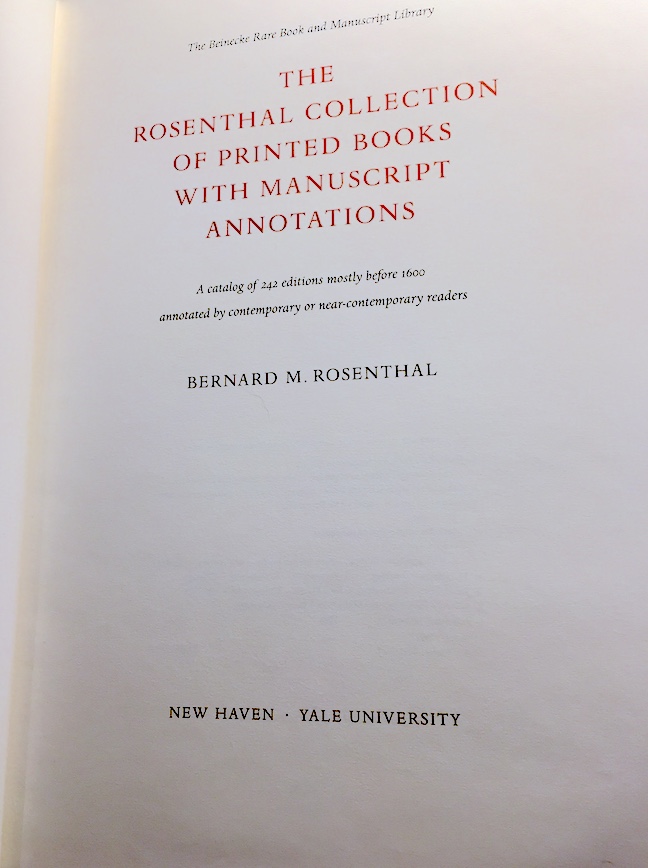

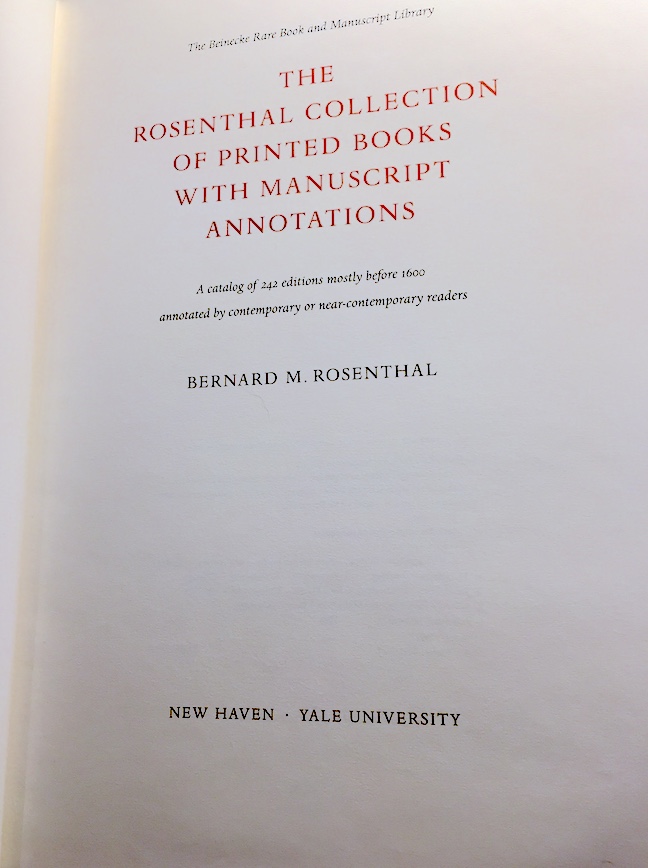

One of Rosenthal’s greatest contributions was his catalogue of a collection of early printed books bearing extensive contemporary manuscript annotations, assembled over several decades and sold en bloc to Yale’s Beinecke Library; the nearly 400 page published catalogue (Yale, 1997) is a pioneering work of meticulous scholarship that sheds much light on Renaissance readership and reading habits. As Rosenthal remarked, “I love to see a book with beautiful wide margins, uncut and untouched. But the grubby book that has been handled and that has thumb marks in it that somebody annotated or otherwise left evidence of reading is really much more attractive.” Rosenthal’s work radically changed the way such annotated books were perceived and was perhaps the greatest factor in creating a new (and pricier) market for such books.

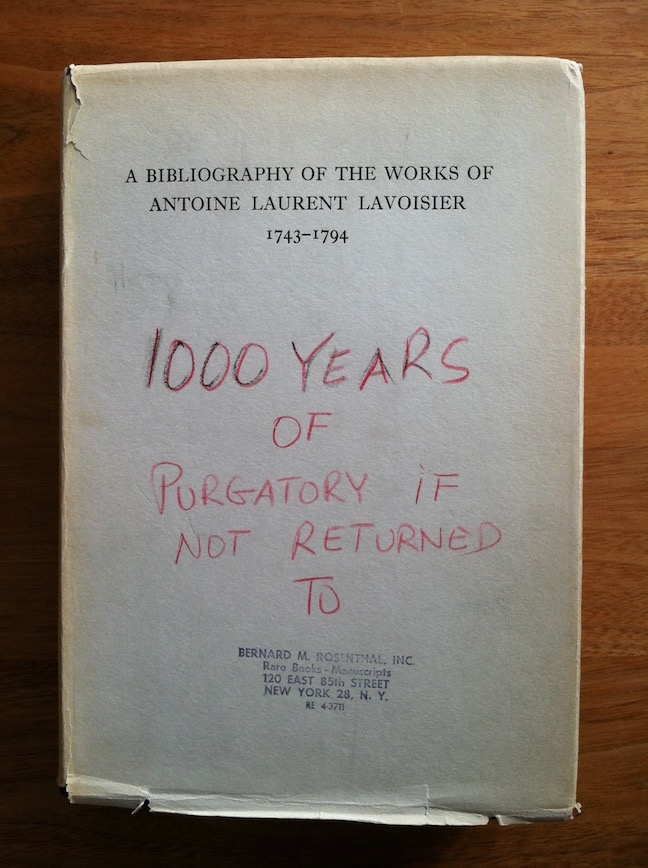

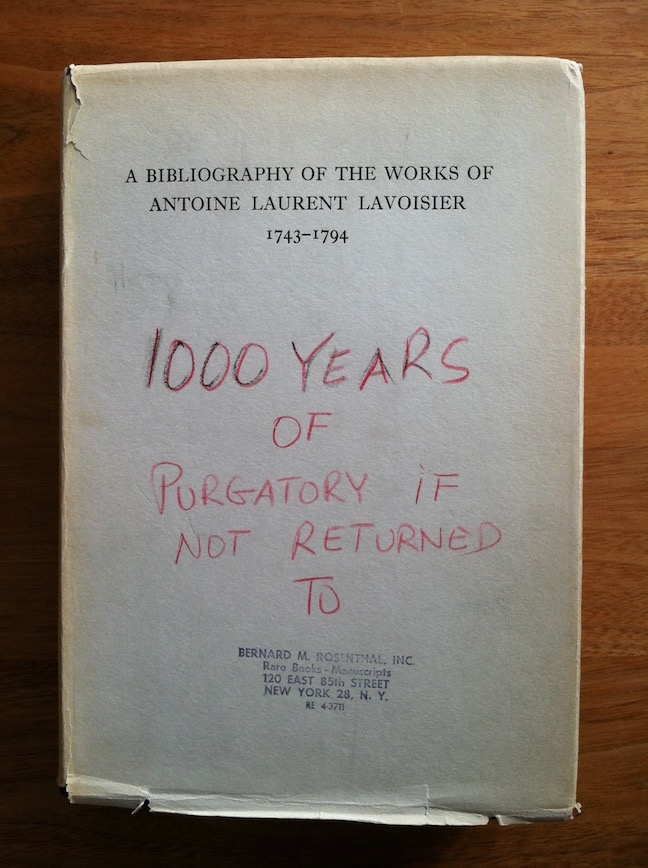

Rosenthal was well known for his generosity, his Old World gentlemanliness, and his wit. Ian Jackson, a Berkeley bookseller, published an account of Rosenthal on the occasion of his 90th birthday. Its title, “The Curse of Bernard Rosenthal,” is in part a nod to all those aspects of Rosenthal’s character, which come together in the “curses” he would pen in books before lending them to his friends, such as “Return to B. M. Rosenthal or be roasted on a spit in the fires of Hell by Satan himself,” written in a copy of a book he loaned to a friend in 1964. Read Jackson’s obituary of Rosenthal...

Hosie Baskin’s copy of the bibliography of Lavoisier. Photo courtesy of Hosie Baskin.

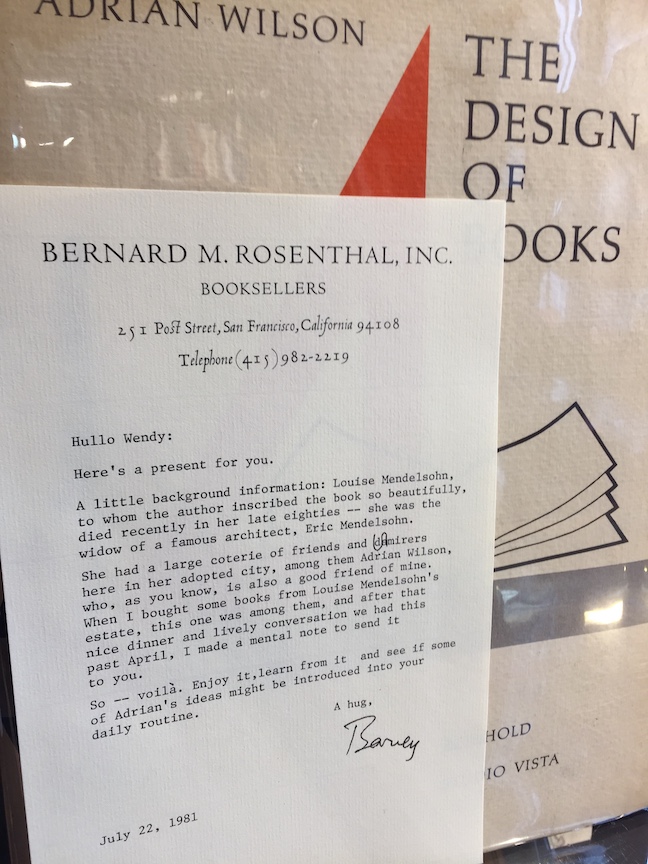

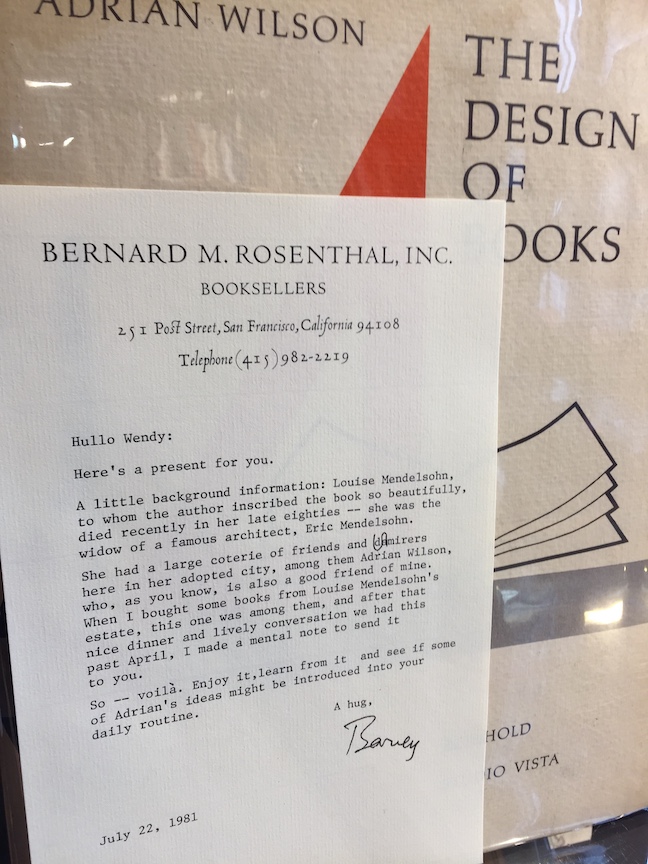

He was also progressive in recognizing that women were just as much book lovers and part of the book world as men. He came from an era that is now regarded as the Old-Boys-Club school of bookselling, which included bibliophilic clubs that were often men-only. But Barney numbered many women among his friends and close colleagues. Jennifer Larson relates how Barney was appalled that San Francisco’s Roxburghe Club of Bibliophiles was off limits to women, and founded The Colophon Club in Berkeley in 1979 in part to give women a place to socialize with booklovers and also to provide a broader and more relaxed quarter for printers, librarians, publishers, illustrators, et al., to hobnob (though, it should be noted, The Roxburghe changed its rules to allow women in 1979). Larson cited the collegial relationship he had with Janet Ing, an acclaimed scholar of early printing, as a typical example. A book we recently purchased, Adrian Wilson’s The Design of Books (1967) came with a delightful note from Rosenthal dated 1981, addressed to a woman named Wendy, recalling a conversation over dinner, and ending, “So – voila. Enjoy it, learn from it and see if some of Adrian’s ideas can be introduced into your daily routine.”

Rosenthal was very optimistic about the future of the antiquarian book trade and the importance of the ABAA’s role in the trade going forward. He was part of a generation of immigrants to the United States that included many other booksellers (Kraus, Salloch, et al.) who played a transformative role in the American rare book trade, discussed with great appreciation in his lecture, “The Gentle Invasion,” which also gave rise to his notion that the younger generation of American booksellers are cultural heirs to the sensibilities and practices of their immigrant forbears.

“I find that there is a tremendous amount of bibliographical and scholarly expertise in the newer generation of booksellers. I’m not at all the person who says that they don’t make them like they used to. I say they make them much better than they used to when it comes to really knowing their reference works and their bibliographies. So I feel very positive about the future of the trade, and if one fine day there are no more medieval manuscripts or there are no more books printed before 1470, well then, there will be lots of other books that you can collect. I think that the rare book trade will pretty much always be with us. Of course, the greatest development, which came a bit late for me to take full advantage of it, is the Internet, but I think again the Internet is a quantitative change. It is an enormous change, but qualitatively, you know, you still have to know how to describe a book and you still have to know how to go about collating it and presenting it properly. But, of course, the bibliographical means that we now have of accessing major library catalogs have made this much easier. The computer is here to stay, but underneath it the qualities, the ethical qualities, remain the same. So, future, positive!”

Booksellers and booklovers everywhere mourn the loss of Barney Rosenthal, and a few of their testimonials and stories can be found below.

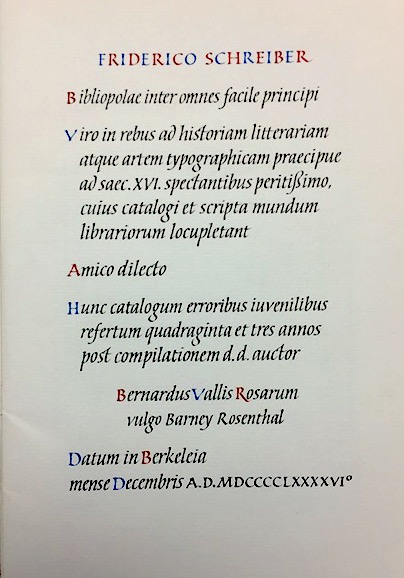

Fred Schreiber:

When, in the early seventies, and still in academe, I published a very modest list—which I presumptuously called a ‘catalogue'—of classical Greek and Latin texts of the out-of-print and used-books variety, I received a letter from a San Francisco bookseller named Bernard M. Rosenthal, whose erudite catalogues I was receiving. The letter was quite complimentary and I was both touched and surprised that my humble production had been taken seriously by such an esteemed veteran antiquarian bookseller. Since I was already toying with the idea of changing careers and entering the rare-book business, but was rather insecure about such a life-changing move, I interpreted Barney’s letter as an encouragement and today attribute to it a major force that prompted my decision to follow my dream.

I’m proud to say that over the years Barney became not only a colleague, but a dear friend as well. I will add only one instance of our abundant correspondence.

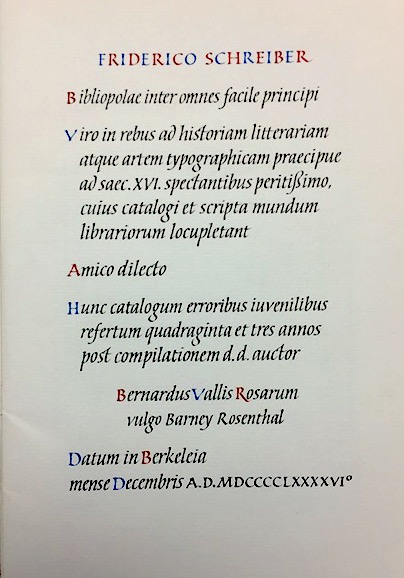

I had asked Barney whether he still had a copy of an old incunabula catalogue he had issued while he was still located in New York City. He said that he thought he did, and that if he located a copy he would send it to me. Several months passed and I had all but forgotten about the incunabula catalogue, when, in December 1996, I received in the mail a thick envelope from Barney containing this catalogue. When I opened it I immediately realized why it had taking him so long to send it to me: on the first blank page, in an elegant calligraphy, was a long Latin presentation inscription:

Carissime Bernarde,

In cordibus omnium qui te amaverunt manens,

Nunquam morieris.

Dearest Barney,

Remaining in the hearts of all who loved you,

You’ll never die.

Joe Luttrell of Meyer Boswell Books:

Barney was a person whom we all sought to emulate and to aspire to be the bookman that he was, impossible as those goals were. I recall visiting Barney's shop on Post Street before I entered the trade, totally diffidently and with very little knowledge, but always to be treated courteously as if I were really an honest to god customer.

After I entered the trade, as a tyro I had the audacity to ask Barney (and Franklin Gilliam) to sponsor my ABAA application. I recall Barney coming over to examine my stock, and that genial bookman indeed gave it a very close look--I then realized if I had not before that behind that most genial of colleagues was an impressive, forceful and knowledgeable person.

The regard which my wife, Sherry, and I had for Barney led us to ask that he officiate at our wedding which, in both English and Italian, Barney generously and gracefully did. Thereafter, one of our mutual friends referred to Barney as "Archbishop Rosenthal".

Those of us who knew Barney were tremendously enriched, and we are now impoverished by his death.

Ed Glaser (Emeritus member and past president, ABAA):

One of the greats has left us. He cannot be replaced. I know of no equivalents to fill the gap. Acknowledged by all to be a giant in the field, he nonetheless had a sweetness and modesty about him that made him instantly approachable. When I moved from the East coast to the West in 1979, Barney led the small, informal delegation that took me to dinner at the North Beach Restaurant to welcome me to the strange new land. We felt we had a special connection because Barney and I were the only members who had been Chairs of the Middle Atlantic and Northern California Chapters of the ABAA at different points in our careers.

Gillian Kyles of Franklin Gilliam Rare Books:

Many years ago, in the mid 1960s, Barney came to the Brick House in Virginia to appraise some of Mr. Mellon’s books—I cannot remember now whether it was the block books which Allan Stevenson had just finished examining; or the early printed books, suffice it to say Barney was with us for quite some time and we all enjoyed his ready wit and also shamelessly sought his advice and expertise.

Just before he was due to return to New York to his small, narrow shop on Madison Avenue, Willis Van Devanter, Mr. Mellon’s librarian, announced one morning at breakfast that he had to go and see a dealer in Covington and a collector of illuminated leaves; he asked if Barney and I would like to go with him. It was a trip of about 200 miles and we would spend the night and come back the following day. In those days there was no Interstate to get us there quickly.

I should mention that each morning we had a rib-bursting full breakfast before waddling off to our offices to work—the mail would be opened at the table and the excuse was that little could be done before the mail arrived, so breakfast was a good idea.

Barney and I both said we would like to see more of Virginia and it sounded like fun. So a few days later accompanied by a groaning picnic hamper we set off. It was a lovely spring day and the countryside had that sparkle and cheer one sometimes gets after a spell of wet weather which we had recently endured. We stopped at a supermarket to get some wine and discovered to our horror that we were in a dry county. Continuing on to Covington, Barney asked Willis about the collector. "Oh a dairy farmer; the house is bare, plastic "dinette" set serves for dining table, linoleum on the floors, minimally furnished—except for the ROOM."

Of course we asked what room.

"Where all the leaves are," said Willis, rubbing the back of his head with the palm of his hand—a frequent Willis gesture. Barney, by this time was leaning over my seat in the front of the station wagon. He seemed a little pale "Tell us more, Willis."

"Well, during the War (WWII) he was stationed near Sutton Coldlfield and one day wandered into a rare book store, where he saw his first illuminated leaves. He literally fell in love at first sight and he has been collecting ever since. The Room is carpeted; it is climate controlled; the custom-made roll-out trays are all lined with baize and no expense is spared to ensure the safety and well-being of the collection".

Barney grew paler and a hint of green was to be detected. "He has written me several times, a rather crude hand on yellow legal paper—I threw them in the waste-paper basket. What am I to do?”

We finally came to the dairy farm, a split-level sitting on top of a bare knoll, not a tree in sight. Barney cowering in the back. We were ushered in and sat down to a marvelous farm dinner. We talked of manuscripts and books generally. Barney, we had introduced as a dealer from London, using his older brother Albi’s name. We had noticed a flicker of interest when we introduced him, but nothing was said.

After our early diner we repaired to the ROOM and Barney was enthralled; he exclaimed again and again over the quality of the collection. It was then that our host told Barney of a New York dealer to whom he had written on several occasions but who had never answered him; he mentioned that his surname was the same as his.

Shock and horror were apparent in Barney’s face which seemed red from anger (of course it was embarrassment): "It must have been my younger brother, Barney. I will write to the young bounder as soon as I get back to London, I cannot think what possessed him not to respond."

Barney was as good as his word: he wrote a long letter, apologizing for not responding, saying that he had had a vendetta with his mailman for years and periodically his mail was not delivered, or misdelivered, or mutilated. It sounded most implausible to me, but he convinced the farmer and they became fast friends and many of the better pieces purchased by this man came from the "brother" of the Man Who Came to Dinner.

I will miss you Barney.

Priscilla Juvelis:

I first met Barney and Albi Rosenthal at a lunch hosted by John Fleming back in (probably) 1984. I know I was honored to dine with these three extraordinary bookman, but I also remember how much fun it was. Barney was the epitome of the old cliché – a scholar and a gentleman – making it true. He was a wonderful colleague – seeing him at ABAA fairs was always a high spot. His smile and kind word for one and all was a delight. He was the very best of us and will be sorely missed.

John Crichton and John Windle:

Barney was a gentle soul, a gentleman, a great bookman and bookseller, and he touched the lives of many in the book world who had the privilege of knowing him, as we did. He will be greatly missed.

Caroline Schimmel:

This is a Barney but not a bookish anecdote: Stuart and I were visiting him in San Francisco in the '70s. It was the beginning of the hanging-fern friendly-waiter craze. The place he took us to for lunch had both. The waiter introduced himself and recited a lengthy list of specials in great loving detail (discussion and eye-rolling ensued among us New Yorkers). When he came back to take the orders, I spoke first and he said "Great choice!"; Stuart next and he said "Great choice!"; Barney last, and he turned and left. It took many minutes for the tears of laughter to stop, at the horror of Barney's selection being a perfectly dreadful choice. We dined out on the tale forever after.

John & Jude Lubrano:

As music antiquarians, we had the distinct pleasure of a close association with Barney Rosenthal’s brother, Albi Rosenthal, for many years. While we, unfortunately, did not have occasion to engage with Barney at any great length, we always enjoyed seeing him at various book fairs and other book- and music-related events to which he inevitably added his idiosyncratic sparkle.

Another proud member of one of the great bookselling “dynasties” of our collective antiquarian booksellers’ souls has fallen and will be greatly missed.

William Reese:

I met Barney Rosenthal when I was seventeen years old. I had just graduated from high school, gotten a car for a graduation present, and taken off from the East Coast to see the books of America. One of my older cousins lived in San Francisco and offered a place to stay, so I was able to settle in and see all of the books of the city. For an Americana boy like me, of course, John Howell Books was the premier location, but my jeans and tennis shoes did not overly impress the management on that first visit (Warren and I later became good friends, but the initial meeting was rather frosty). I worked my way down Post Street and wandered into Barney's. I didn't know much about anything, and certainly not incunables, but I was trying to learn my way around bibliography. Far from booting me out, Barney rolled out the red carpet. He showed me around and let me look to my heart's content, keeping up a stream of questions about my interests, my plans, and my life. It probably helped that his gentle queries revealed I was going to Yale in the fall, where he of course knew many people, but I doubt if it would have made a difference. Then he took me next door and introduced me to Franklin Gilliam, another bookseller who became a lifelong friend. Then they invited me to lunch! And all the while, acted as if I was an knowledgeable adult! Lord knows what kind of fool I may have made of myself; if so, they were kind enough to never bring it up later. It was the best day of my life in books to that point, and the first of many happy visits, and lunches. We never did much business, being in opposite spectrums of the book world, but I felt we always saw things from the same perspective. He was a man of myriad kindnesses, large and small. I am proud to have had him for a friend for over four decades.

****

Bernard M. Rosenthal was born in 1920 in Munich. Most of his immediate family left Munich for Florence in 1933, left Italy for France in 1938, and arrived in the US in 1939, each move in response to the problem of being Jewish. Both sides of his family, the Rosenthals and on his mother’s side, the Olschkis of Italy, were heavily involved in the book trade going back generations as antiquarians, printers, publishers and authors. An

Bernard M. Rosenthal was born in 1920 in Munich. Most of his immediate family left Munich for Florence in 1933, left Italy for France in 1938, and arrived in the US in 1939, each move in response to the problem of being Jewish. Both sides of his family, the Rosenthals and on his mother’s side, the Olschkis of Italy, were heavily involved in the book trade going back generations as antiquarians, printers, publishers and authors. An