The streets of Dublin witnessed the largest parade in Irish history this Easter, as hundreds of thousands gathered to mark the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising. That revolt, by historical standards, was brief and seemingly futile in the short term. After the April 24 proclamation of an Irish Republic, perhaps fewer than 2,000 participants actually took up arms, and they were easily crushed within days by the British bombardment of much of central Dublin and the surrender and execution of its leaders. Nevertheless, the Rising boasts an outsize legacy not only in its ultimate political consequence of Irish independence five years later, but in its literary birthright, for a number of those involved in the uprising were authors of poetry and prose that had sculpted perceptions of Irish nationhood. Moreover, the destruction wrought upon Dublin and the execution of the rebel leadership inspired others who had not been involved – even some who had looked upon the armed uprising in dismay – to grapple with its legacy in words that resound to this day.

The struggle for Irish independence from the British Crown had surged and ebbed for many years, of course, one of the high points being the months of battles led by the United Irishmen in 1798, inspired by the successful revolutions in the American colonies and in France. By the 1910s, however, many had thought that the flame of discontent had shrunken to a dull gleam. Although the House of Lords had failed to pass a Home Rule Bill in 1913, the margin had been close, and by 1914 it was adopted with royal consent – only to be suspended with the outbreak of the First World War. Most Irish sympathized with the Allies in the war, and many counseled that patience would bring victory for Irish Home Rule. Even many of the Irish Volunteers, a nationalist paramilitary organization, had decided that aiding the British war effort was the surest path to eventual recognition once hostilities had ceased.

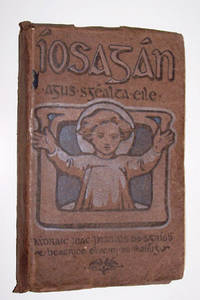

A culturally-oriented nationalism, whose proponents included the poet William Butler Yeats, motivated a large sector of the Irish Republican movement. The Gaelic Revival sought to return the Irish language to vitality after decades of the growing dominance of English. Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais, known in English as Patrick Henry Pearse, emerged from this cultural milieu, writing extensively on matters linguistic and literary. Among his early contributions was the publication of stories in Irish Gaelic. ABAA member William F. Hale-Books currently offers a 1907 collection, “Íosagán agus Sgéalta Eile,” published in Dublin. This particular copy includes pencil marginalia reflecting the struggle of an English-speaking student to master the Gaelic vocabulary.

Íosagán agus Sgéalta Eile

by Mac Piarais, Padraic

Dublin: Conradh na Gaeilge. Good+. 1907. First Edition; First Printing. Softcover. 3 p.l., 117 & [2] pages; Publisher's brown pictorial wrappers, title page printed in red and black (dated "1907"), edges of the text trimmed rough. (Offered by William F. Hale-Books)

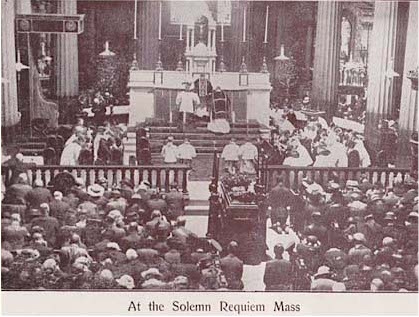

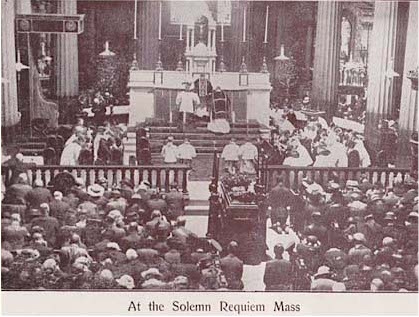

Pearse linked this linguistic and literary movement to more forthright confrontations with British power. In his conception, an Irish revolution would draw from both cultural and military resistance. In 1913 he had participated in the inaugural meeting of the Irish Volunteers, a group affiliated with the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood, whose membership included a number of significant writers. One of the keystones of a collection on the Easter Rising would surely be Pearse’s oration from the funeral of longtime independence activist Diarmuid Ó Donnabáin Rosa in 1915. Pearse took this opportunity to signal the possibilities of a new era of armed action. The oration was included in an illustrated souvenir booklet together with pieces by Thomas MacDonagh, Arthur Griffith, James Connolly and Brian O'Higgins, published by the O'Donovan Rossa Funeral Committee. These are reasonable affordable, appearing at auction from time to time in the range of $150-200 or the Euro equivalent. One of the illustrations in the pamphlet depicts the solemn splendor of the funeral, a striking setting for Pearse’s pledge that “This is a place of peace, sacred to the dead, where men should speak with all charity and with all restraint; but I hold it a Christian thing, as O'Donovan Rossa held it, to hate evil, to hate untruth, to hate oppression, and, hating them, to strive to overthrow them. Our foes are strong and wise and wary; but, strong and wise and wary as they are, they cannot undo the miracles of God who ripens in the hearts of young men the seeds sown by the young men of a former generation.”

Another trend in the Irish independence movement was revolutionary socialism, which was not as interested in romanticizing the nation as a mythic, sacred entity. Rather, its partisans perceived Irish self-rule as part of an international movement to defend the rights of workers and farmers.

Another trend in the Irish independence movement was revolutionary socialism, which was not as interested in romanticizing the nation as a mythic, sacred entity. Rather, its partisans perceived Irish self-rule as part of an international movement to defend the rights of workers and farmers.

James Connolly, the founding editor of a newspaper titled The Socialist, co-founded the Socialist Labour Party in 1903, but soon thereafter headed to the United States where he played an active role in both the American SLP and the Industrial Workers of the World. Connolly returned to Ireland in 1910 and, with Jack White, founded a small armed group, the Irish Citizen Army, originally to defend striking workers from the often brutal Dublin police. From this beginning the ICA became another force for armed rebellion against British rule, on a more secular and internationalist basis.

Connolly’s views on labor and Ireland are expounded in this book, Labour in Ireland, which was published the year after his execution. Connolly’s thought remains influential on the Irish (and American) left to this day, and his essays have been republished in countless forms. It would be easy to build a substantial collection of pamphlets and books reprinting his works.

Thus it was that in the midst of a broader movement of literary and artistic celebration of Irish culture (discussed at length in Declan Kiberd’s Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation), men like Pearse and Connolly organized for rebellion of a more urgent form. Leaders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood including Tom Clark and Pearse met with Connolly in early 1916 to plan for an Easter uprising that would combine their forces. A nationwide uprising planned for Easter Sunday was aborted amid miscommunication and confusion, but the central organizers in Dublin decided to move ahead the following day, Easter Monday, and to hope for a groundswell of support to bring success to their enterprise.

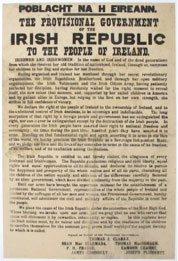

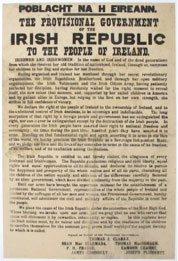

Volunteers mustered with arms at sites around Dublin, and Pearse formally read a proclamation of the Irish Republic from the hastily established headquarters at the General Post Office in Dublin. Handbills with the text of the proclamation had been prepared the previous evening, printed using a borrowed font of type at Liberty Hall on sheets of the inexpensive paperstock that Connolly purchased in bulk for his newspaper. Approximately fifty examples of this leaflet are thought to survive today, some of which have been extensively repaired or glazed to prevent the acidic paper from disintegrating. The Irish firm Whyte’s, which recently held a major auction of Easter Rising material to mark the centenary, netted 185,000 euros for the creased copy of the Proclamation leaflet seen on the right.

Volunteers mustered with arms at sites around Dublin, and Pearse formally read a proclamation of the Irish Republic from the hastily established headquarters at the General Post Office in Dublin. Handbills with the text of the proclamation had been prepared the previous evening, printed using a borrowed font of type at Liberty Hall on sheets of the inexpensive paperstock that Connolly purchased in bulk for his newspaper. Approximately fifty examples of this leaflet are thought to survive today, some of which have been extensively repaired or glazed to prevent the acidic paper from disintegrating. The Irish firm Whyte’s, which recently held a major auction of Easter Rising material to mark the centenary, netted 185,000 euros for the creased copy of the Proclamation leaflet seen on the right.

The Volunteers failed to occupy Dublin’s train stations, and thousands of British soldiers were able to gather on short notice, rebounding from the complete surprise of the Rising’s first day. Rather than directly assaulting the Volunteer positions in the urban center, the British bombarded them, with extensive collateral damage to surrounding buildings and infrastructure.

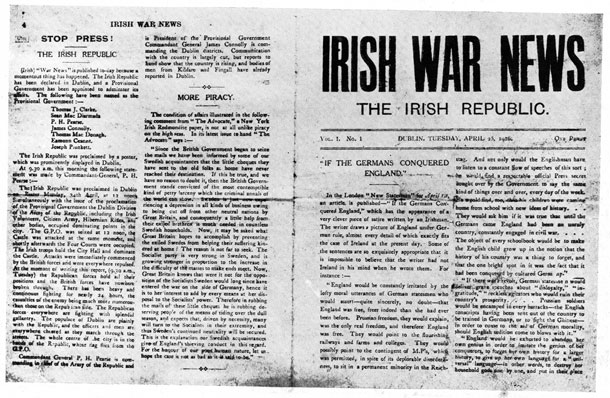

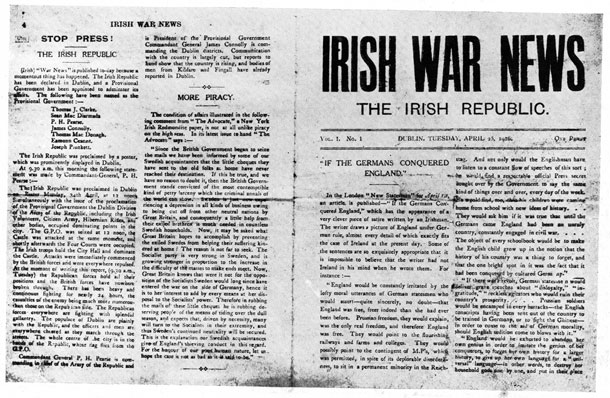

Any publication from the days of the Rising is extremely rare, though the mere mortal can afford examples of newspapers from the time reporting on the progress of the revolt and its suppression. The same auction noted above included a broadside announcing martial law in Ireland, issued by the government during the Rising, which sold for 2,100 Euros. A short-lived newspaper of the Republican forces, “Irish War News,” gave its place of publication as The Irish Republic. Issues are scarce.

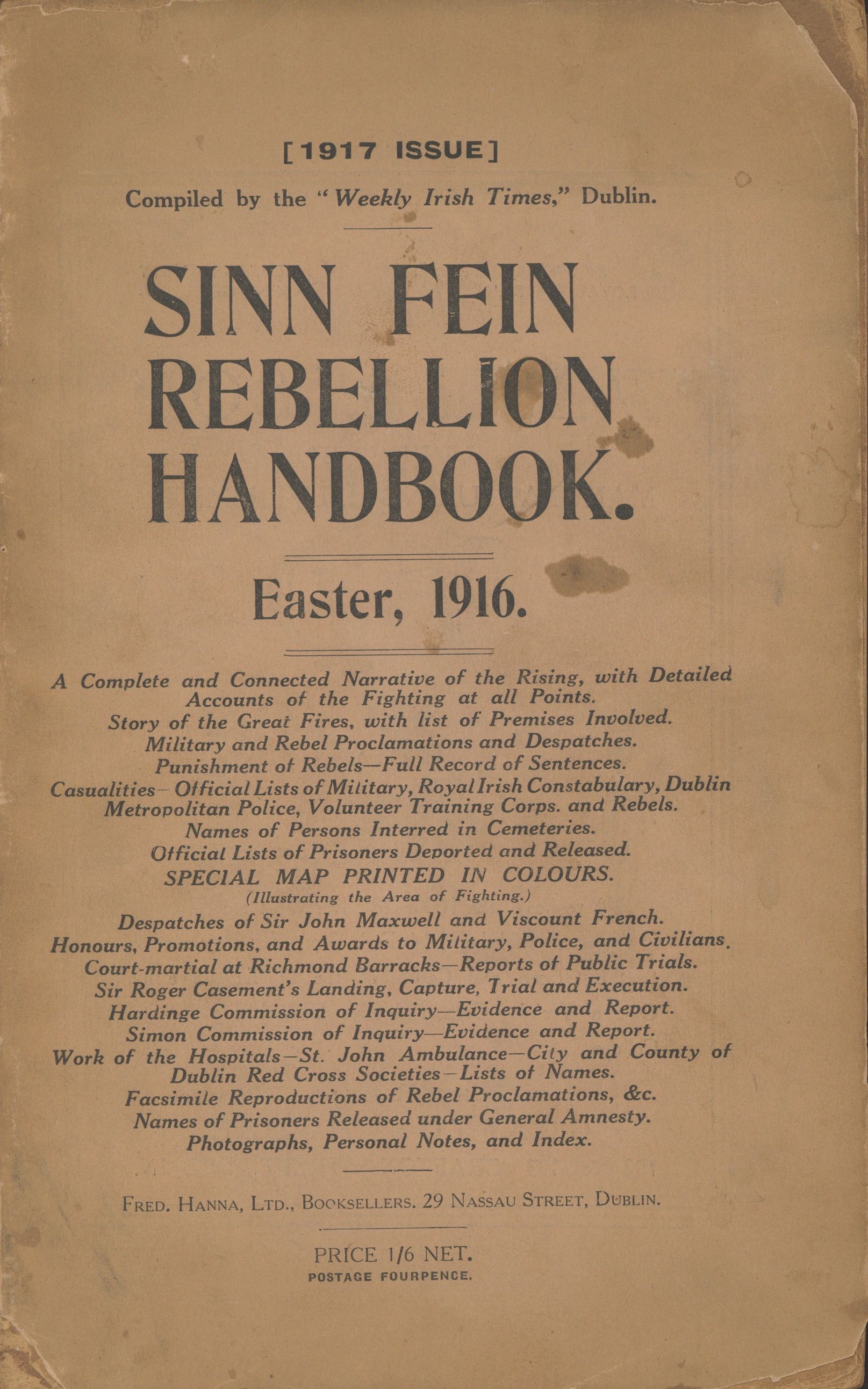

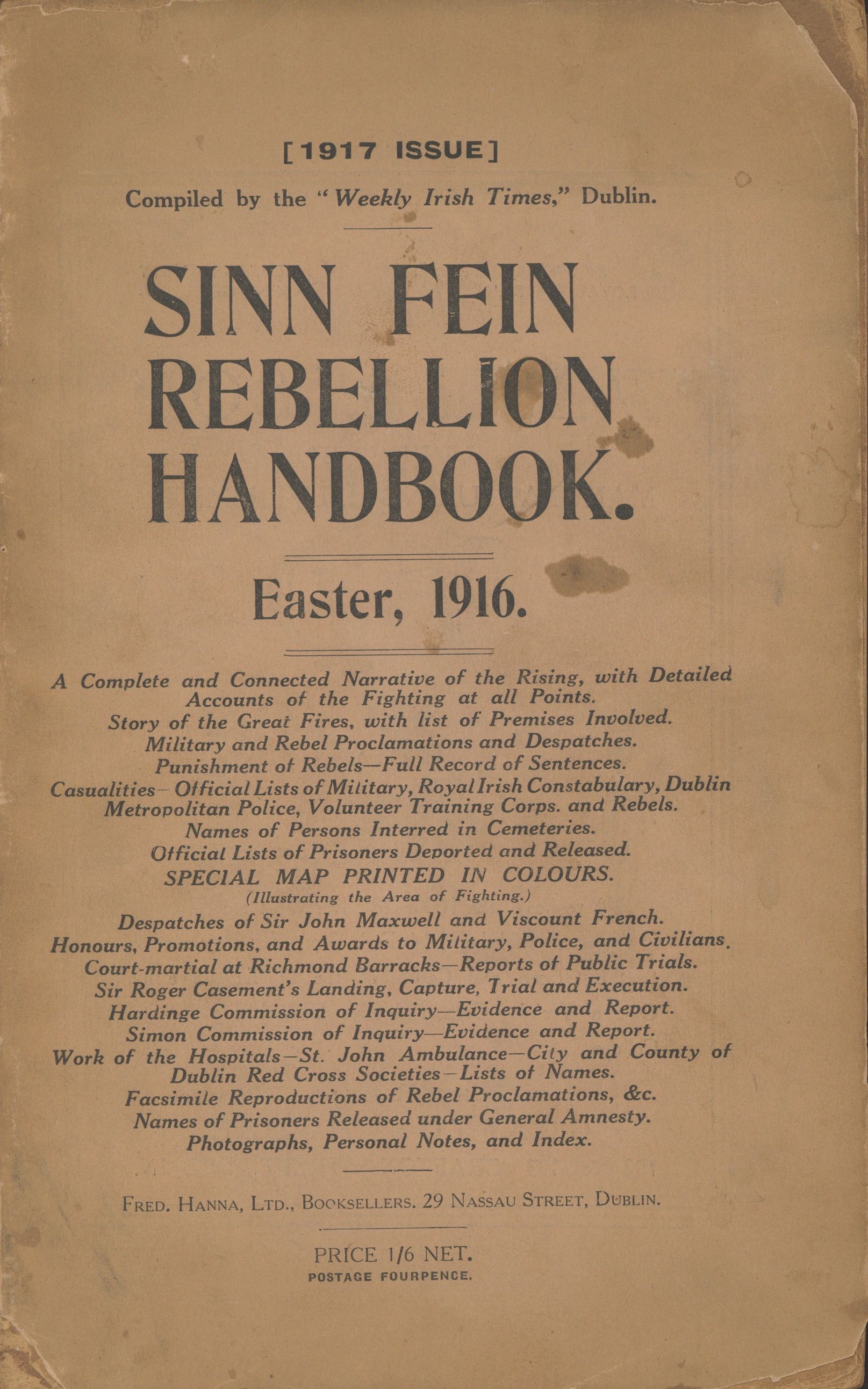

Local publishers also made the most of the opportunity to issue commemorative booklets or souvenir editions. The Irish Times, published in Dublin, gathered reportage and illustrations to create the “Sinn Fein Rebellion Handbook. Easter 1916,” described as “A Complete and Connected Narrative of the Rising, with detailed accounts of the fighting at all points.”

Sinn Fein Rebellion Handbook. Easter 1916. A Complete and Connected Narrative of the Rising , with detailed accounts of the fighting at all points.

By Sinn Fein Weekly Irish Times

Dublin: The Irish Times, 1917. Octavo, xvi, 286 pages. Folding map in color. First edition. One of the key sources for information about the Easter uprising, based on material from the Irish Times of 1916. With a fold-out color coded map showing the locations of events in Dublin. Fragile, as usual, and with the original wrappers brittle and detached. Still, quite rare in the wrappers. (Offered by Rabelais Fine Books)

After six days of fighting, heavy civilian casualties (around half of the 500 who died were non-combatants) and great destruction of property, Pearse issued the order to surrender, “In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered.” London, incensed at the insurrection in the midst of its war against Germany, had the instigators tried for treason and executed. Many who had been critical of the Rising’s timing and methods were ultimately swayed by the British response to it to endorse a more militant nationalism.

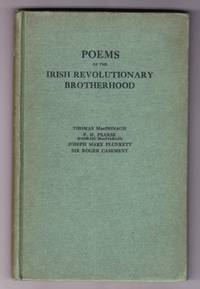

A collection, “Poems of the Irish revolutionary brotherhood,” was published in Boston, an epicenter of Irish expatriate activity, soon after the Rising had been suppressed. After introducing the recently-fallen poets Patrick Pearse, Joseph Plunkett, Thomas MacDonagh and Roger Casement, the introduction highlights their combination of martial and literary prowess: “These are poems by Combatants… No attempt need be made to estimate the achievement of the poets of this anthology. An Irishman knows well how those who met their deaths will be regarded. ‘They shall be remembered for ever; they shall be speaking for ever; the people shall hear them for ever.’"

Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood

Edited by Padraic Colum & Edward J. O'Brien

Boston: Small, Maynard and Company, 1916. First edition, first prnt. Green printed paper-covered boards. 60pp including Bibliography and endpages. Poems by Thomas MacDonagh, P.H. Pearse (Padraic MacPiarrais), Joseph Mary Plunkett and Sir Roger Casement. Introduction by Padraic Colum. (Offered by Revere Books)

The most famous poetic tribute to the Rising comes not from any of its members but from W.B. Yeats, a major figure in the Gaelic cultural movement who watched aghast as the armed rebellion took shape and was crushed. He was among those Gaelic nationalists who believed that patience through the war would result in the eventual implementation of Home Rule that had been frozen by the outbreak of hostilities. As he suggests in “Easter, 1916,” “For England may keep faith /For all that is done and said.” It is precisely this emotional distance that renders his tribute the more poignant. Even men he despised, like Major John MacBride (who had abused Maud Gonne, a woman Yeats loved, and molested her daughter) took on the aura of martyrs after dying for the cause of Irish independence:

“This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vain-glorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.”

Yeats’ poem was first published in 1920, in the collection “Michael Robartes and the Dancer” (Dublin, Cuala Press). First editions are difficult to come by – at present we find only one listed in England for close to $900 – but this poem has been republished in enough anthologies to be worth a collection unto itself.

The executions of the leaders of the Rising served only to cement their legacies, as their essays, poetry and stories have been reprinted time and again in various formats, offering the collector on a budget the opportunity to assemble and enjoy a library that would be impossible in first editions. Many anthologies include relevant contributions, such as this 1924 collection published in New York, “Songs of Ireland.”

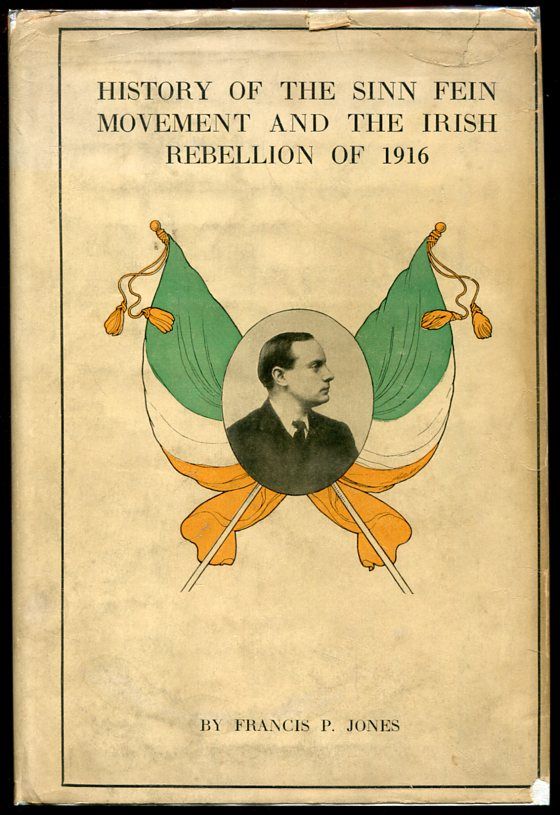

Almost as soon as the ashes had cooled in Dublin, historians turned to the causes of the Rising and the process of its unfolding. Here is an early survey, “History of the Sinn Fein Movement and the Irish Rebellion of 1916,” offered by ABAA member Appledore Books:

History of the Sinn Fein Movement and the Irish Rebellion of 1916

by Francis P. Jones

New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons, 1917. 1st. Cloth. Collectible; Very Good/Very Good. (Offered by Appledore Books)

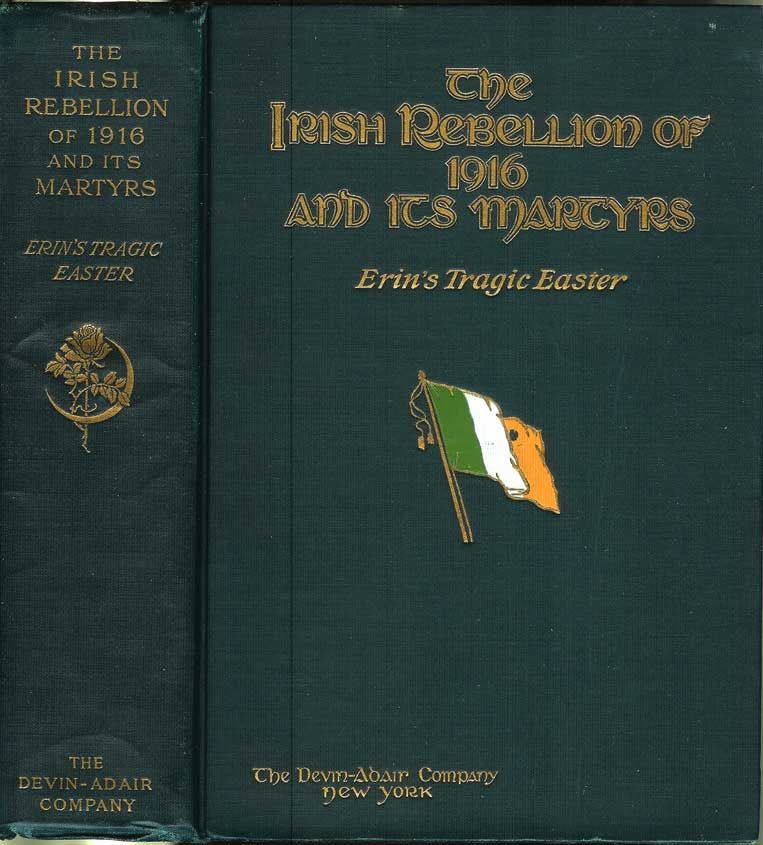

This sympathetic account, “The Irish Rebellion of 1916 and its martyrs: Erin's Tragic Easter,” also published soon after the Rising, is offered by Chanticleer Books:

The Irish Rebellion of 1916 and Its Martyrs

Edited by Maurice Joy

New York: Devin-Adair, (1916). First edition. About fine, ink stamp of Benedictine Press on title page. (xiv), 427 pp., [7] pp. ads at rear, many plates from photographs, folding map of Dublin; 8vo, green cloth with gilt titles and Irish tri-color flag ornament on front board. Accounts of the Easter Rising of 1916 and the events leading up to it. (Offered by Chanticleer Books)

Among the best-informed popular histories from later decades is Max Caulfield’s 1965 classic, “The Easter Rebellion” (London: New English Library). Published in time for the fiftieth anniversary, the book made extensive use of interviews with surviving participants in the rebellion as well as members of the Crown forces who had helped to put them down. It is easily obtainable today.

A more recent work by Charles Townshend, “Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion” (London: Allen Lane, 2005), has become the go-to starting point. It is too recent to be found in the stocks of most ABAA dealers, but can be obtained with ease, either new or used.

Volunteers mustered with arms at sites around Dublin, and Pearse formally read a proclamation of the Irish Republic from the hastily established headquarters at the General Post Office in Dublin. Handbills with the text of the proclamation had been prepared the previous evening, printed using a borrowed font of type at Liberty Hall on sheets of the inexpensive paperstock that Connolly purchased in bulk for his newspaper. Approximately fifty examples of this leaflet are thought to survive today, some of which have been extensively repaired or glazed to prevent the acidic paper from disintegrating. The Irish firm Whyte’s, which recently held a major auction of Easter Rising material to mark the centenary, netted 185,000 euros for the

Volunteers mustered with arms at sites around Dublin, and Pearse formally read a proclamation of the Irish Republic from the hastily established headquarters at the General Post Office in Dublin. Handbills with the text of the proclamation had been prepared the previous evening, printed using a borrowed font of type at Liberty Hall on sheets of the inexpensive paperstock that Connolly purchased in bulk for his newspaper. Approximately fifty examples of this leaflet are thought to survive today, some of which have been extensively repaired or glazed to prevent the acidic paper from disintegrating. The Irish firm Whyte’s, which recently held a major auction of Easter Rising material to mark the centenary, netted 185,000 euros for the