To mark the 75th Anniversary of 1939, we've asked some ABAA members to discuss publications from that momentous year. Jim Dourgarian, a specialist in Steinbeck (among other authors), recounts his experiences reading and selling The Grapes of Wrath.

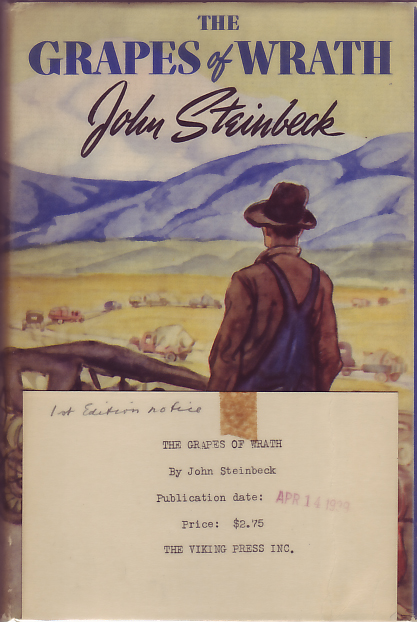

The 1930s were a turbulent and momentous decade for John Steinbeck. He published such diverse and quality books as The Pastures of Heaven, Tortilla Flat, In Dubious Battle, Of Mice and Men, The Red Pony, and finally, on April 14, 1939, his masterpiece— The Grapes of Wrath.

I had been introduced to Steinbeck as a high school freshman. My English teacher said we could read only one of his books per semester because he was “too brutal,” but brutal was exactly what I wanted. I was hooked.

Steinbeck spoke for the underdog, the oppressed— and that was me! And many of the people who populated his books seemed to be my people. Both sets of my grandparents were poor. They struggled mightily, all while maintaining their dignity and belief in hard work.

Eventually I read The Grapes of Wrath. It’s a 600-page book, and I am not a speed reader, but I liked the story. And I even liked wading through the inner chapters wherein Steinbeck writes of man’s struggle and agricultural politics.

I probably read it for the first time in the equally turbulent 1960s. Comparing those decades, the 1930s and the 1960s, was a revelation. Not much had changed. The Man still oppressed the people. The fear of communism was ever-present. Rage against the Machine still festered.

Reading the book became an intellectual exercise for this then-young man. I found that as I read it, my own intellect seemed to grow as the book progressed. That alone was memorable, but as I neared the end of the book I asked myself how would he end the book. It has no real plot. I hate books that just come to an end. I wanted punch. And I got it. In spades. I was blown away. I didn’t see it coming. I couldn’t believe “they” would allow such an ending. Steinbeck’s editor and his agents both argued against it. Steinbeck insisted on his ending. The world is better for him standing his ground. I won’t reveal the ending for any of you who haven’t actually read the book, but I will promise you this: it is memorable.

I re-read the book a couple of years ago. It stood up, even though I was a much older and experienced reader this time around, and I already knew the ending. I was still blown away by the entirety of it, the story, the quality of the writing, and that ending. I remembered the strength of Ma Joad, but I had forgotten just how strong she was in keeping that family together as best she could. I finally saw

Ed Ricketts, Steinbeck’s best friend and philosophical mentor, in the character Jim Casy. Ricketts made several appearances in Steinbeck’s books over his career, but I understood the character, and saw Ricketts, better in my second reading. This made for even greater appreciation of the book.

Is it his best book? It did win the Pulitzer, Steinbeck's only Pulitzer win. It would be hard to argue against it, although there are rivals, chief of which might be The Pastures of Heaven. The book was both hated and revered in 1939 and for years after as well. California’s agricultural owners hated it. Steinbeck was labeled a communist. Threats were made. And yet the people loved it. The book sold, like crazy. Steinbeck himself had been exhausted by his burst of intellectual and creative action in writing the book. He was not prepared for the extremes it produced, from hatred, to a California state senator’s wife writing a book about how workers were cradled in love by farm owners and that Steinbeck’s book was nonsense, to it being championed by none other than Eleanor Roosevelt.

As a bookseller, I’ve encountered and handled a number of special copies. I have a

first edition inscribed to another writer. I have the

only first edition review copy with a review slip I have ever seen. Steinbeck had 10 copies specially bound to be auctioned to benefit farm workers. Steinbeck was to have inscribed the book to the auction winner. I had one once, but it must have been an unsold copy as it wasn’t signed. I nearly acquired another one that was inscribed to actor Edward G. Robinson, but it managed to elude me. That’s a story for another day.