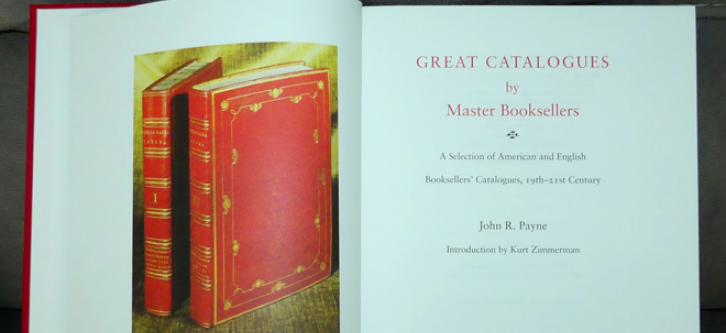

Great Catalogues by Master Booksellers: A Selection of American and English Booksellers’ Catalogues, 19th-21st Century. By John R. Payne. Introduction by Kurt Zimmerman. Austin [Tex.], Roger Beacham, Publisher, [2017].

One could be forgiven for thinking it odd that something as ephemeral as the bookseller’s catalogue should be treated to such a sumptuous production as John Payne’s Great Catalogues by Master Booksellers (GCMB). But, as the author reminds us, “Bookshops open and close. Booksellers retire, change professions, and pass on. What remains, other than memories and reputations, are their catalogues, the lasting tangible record of a bookseller’s creativity and expertise – a remembrance, a talisman.” (Preface, page xi).

One could be forgiven for thinking it odd that something as ephemeral as the bookseller’s catalogue should be treated to such a sumptuous production as John Payne’s Great Catalogues by Master Booksellers (GCMB). But, as the author reminds us, “Bookshops open and close. Booksellers retire, change professions, and pass on. What remains, other than memories and reputations, are their catalogues, the lasting tangible record of a bookseller’s creativity and expertise – a remembrance, a talisman.” (Preface, page xi).

The author has selected one hundred forty catalogues from amongst tens of thousands viewed during his time at the Lilly Library at Indiana University, The Harry Ransom Center at University of Texas at Austin, New York’s Grolier Club, and the Huntington Library in San Marino. The individuals and firms represented include the giants of the last one hundred fifty years of bookselling, names such as Breslauer, Eberstadt, ExLibris, Les Enluminures, Fleming, Goldschmidt, Goodspeed, Kraus, Maggs, Quaritch, Reese, Rosenbach, and Rostenberg & Stern, as well as more contemporary booksellers who will be seen in retrospect, if they are not already, as giants themselves. An introduction by Kurt Zimmerman briefly outlines the impact booksellers’ catalogues has had on the formation of collecting fields including Western Americana (Eberstadt), Victorian Fiction (Pickering & Chatto), and the History of Science (Scribners under John Carter and David Randall). And while Zimmerman touches on the shift away from printed catalogues in the digital era, the work shows more recent generations of booksellers blazing new paths in collecting and scholarship, amongst them ExLibris with their monumental Russian Futurism or J. N. Herlin’s Brain Storms, the first to explore conceptual artist books. Other new-ish catalogues represent a new technology or format, such as Ben Kinmont’s 2002 Eat Drink & Be Merry! A Holiday List of Gastronomy, purportedly the first catalogue to be issued on CD-ROM, a digital format both doomed to be quickly superseded and simultaneously too futuristic for the mostly non-tech-savvy crowd that was the audience for most antiquarian catalogues in 2002.

Each of the items in GCMB is represented by an image of the catalogue’s cover, and sometimes by additional images of the bookseller, or by photographs of the very special items on offer within. Descriptions of the catalogues include basic bibliographic information and lengthy – often complete – quotes drawn from the introductory matter of the catalogues themselves. It is these introductions, frequently supplied, not by the booksellers, but by a scholar, collector, librarian or other expert, which contextualize the catalogues, though having been created for the catalogue, they are unable to offer historical perspective on the reception or impact a catalogue may have had. A backward glance is provided in a few cases from the listings of later booksellers who have listed these catalogues for sale via online listing services. Citing an online book listing – a listing that necessarily evaporates with a sale – makes me a bit uncomfortable, but it serves as a nod by the author to the odd moment in which we find ourselves as antiquarian booksellers, one in which the printed catalogue may seem quaint in the face of the currently available online listing, publishing, and email marketing tools, and in which the efforts of the bookseller, scholarly or mercantile, often leave behind no record.

As much as many catalogues in GCMB have contributed to canon development in their respective fields, Payne’s work is itself in the same business. Before my first reading of GCMB was completed, I was compiling lists in my mind of which catalogues I possess and which I may have recently seen and might still easily acquire. This was quickly followed by that queasy realization that some items I once owned may have been carelessly disposed of along the way, and yet now these catalogues are cemented into the canon of desirability. Drat! Further, a list like GCMB immediately leads many of us to start quibbling. Where are James Jaffe’s catalogues? What about the Vietnam War Literature or Native American Literature catalogues of Ken Lopez? There are so many others, but in the face of the work presented here, this is mere quibbling. GCMB has provided a bulwark for us to push against, so that we might lobby for inclusion of those booksellers and catalogues missing, and perhaps more importantly, so that we might aspire to such greatness with our own catalogues.

On one point, I have more than a quibble. Only two of the items are illustrated with an image of a catalogue description itself. Certainly, the heart of a catalogue is the manner in which a bookseller chooses to display the complicated sorts of information contained in an item description. There is little uniformity of approach from bookseller to bookseller, and even less from subject to subject. For example, cataloging modern first editions requires a different method than cataloging early works in the history of technology; through time booksellers change their cataloguing approaches to reflect their own styles and the needs of their various audiences. Fortunately, the two examples offered, one for H.P. Kraus’ The Cradle of Printing and the other for Serendipity Book’s American Fiction of the 1960s appear to be near polar opposites of information selection and display, and illustrate how interesting a few more images of other booksellers’ catalogue descriptions may have been. There are two other major modern selective surveys of the bookseller catalogue, both produced by antiquarian bookseller and scholar Jurgen Holstein. Bücher, Kunst und Kataloge: Dokumentation zum 40 jährigen Bestehen des Antiquariats (Berlin 2007) and Goldrausch & Werther: Antiquariatskataloge als Sonderfall des Umschlagdesigns / Antiquarian Catalogs - a Special Case in Cover Design (Berlin 2014) are both similarly monumental in aspect to GCMB, while drawing from a more international pool of catalogues; they are both similarly guilty of largely overlooking the cataloguing itself. The second volume is given solely to consideration of the cover designs of these catalogues, itself a worthy subject, but I remain puzzled as to why such little consideration of the inner workings.

Despite this one weakness, John Payne’s work joins that of Holstein in drawing the attention of collectors, librarians, and booksellers to this history of booksellers and the books they sell, as revealed through the rich vein of historical evidence the catalogues provide. In Bookshops, A Reader’s History (Eng. translation 2017), author Jorge Carrion speaks of the addition of a book to a shop’s shelves as a bookseller’s act of “consecration”. In the hands of a “Master Bookseller” it seems that a book’s sacrament is rather its description and inclusion in the “Great Catalogue”. Though not a bookseller’s catalogue itself, GCMB rises to the level of great catalogue, and it offers us a journey back through decades of the best of the field of antiquarian bookselling while providing a roadmap forward of catalogues to pursue and collect.

View the latest catalogs from the members of the ABAA...

One could be forgiven for thinking it odd that something as ephemeral as the bookseller’s catalogue should be treated to such a sumptuous production as John Payne’s Great Catalogues by Master Booksellers (GCMB). But, as the author reminds us, “Bookshops open and close. Booksellers retire, change professions, and pass on. What remains, other than memories and reputations, are their catalogues, the lasting tangible record of a bookseller’s creativity and expertise – a remembrance, a talisman.” (Preface, page xi).

One could be forgiven for thinking it odd that something as ephemeral as the bookseller’s catalogue should be treated to such a sumptuous production as John Payne’s Great Catalogues by Master Booksellers (GCMB). But, as the author reminds us, “Bookshops open and close. Booksellers retire, change professions, and pass on. What remains, other than memories and reputations, are their catalogues, the lasting tangible record of a bookseller’s creativity and expertise – a remembrance, a talisman.” (Preface, page xi).